There is very little that Western governments – or climate activists – can do about the future of coal.

With most of coal consumption being in India and China – and a significant part of the rest in Southeast Asia – the future of the resource is largely beyond the reach of Western climate policies.

According to the International Energy Agency (p. 11), China alone accounts for more than half of global coal demand (53%).

China and India together account for 70% of demand, with other countries from the region bringing the share up to more than three quarters.

And while Europeans – and especially Germans – are quick to leave the commodity behind, those countries follow a different strategy.

They believe, instead, that renewables will not be implemented fast enough to cover the region’s growing energy appetite.

This causes them to turn towards oil and gas – for which established infrastructures are already in place.

And with gas supplies probably remaining more expensive at least over the next years, the future of coal in the region seems save.

This is certainly the view of recent scenarios on Asia Pacific’s energy future.

Energy analysts at Wood Mackenzie state that 14% of the power generated across the whole Asia Pacific Region in 2050 will come from coal.

This will bring coal only to the third place after wind and solar – contributing considerably less the renewables to the region’s power supply.

But it is still a significant share – and more than the analysts projected in 2022.

On a global level, the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts coal consumption to remain stable at slightly above eight billion tons through 2025.

While this leaves open the possibility of a global decline in the second half of the decade, it is a far cry from full-fledged exit from coal that countries like Germany pursue.

And data published by the Global Energy Monitor confirms that this stability mainly emerges from the expansion of coal-based power generation by China.

In 2022, 59% of the overall 45.5 gigawatt (GW) of newly commissioned coal power plant capacity came from China.

In 2022, the country had 366 GW under development, up by 38% from the 266 GW in 2021.

This compares to 172 GW of capacity under development in the rest of the world, which is 20% less than in 2021 (214 GW).

This includes Europe, where, despite reports about a ‚renaissance of coal‘, the EU did not increase its investments in coal power plants.

Instead, the 2022 energy crisis only slowed down the rate of decline for the energy source.

Energy suppliers throughout the Union shut down a capacity of 2.2 GW, instead of the record 14.6 GW of the year before.

But this still means that the continent is on its way to leave coal behind, even when gas become extraordinarily high.

Most retirements came, however, from the US, with a capacity of 13.5 GW being closed.

In fact, without China’s ongoing expansion, global coal power generation capacity would be declining globally.

With that expansion, however, coal is going to contribute to global energy supply for the foreseeable future.

According to the GEM, 70% of all coal power plants in the OECD are on track to be closed by 2030, the key date for developed countries in the UN’s new ‚Acceleration Agenda‚.

Reflecting their overall structurally different treatment of coal, countries outside of the OECD plan to close only 6% of their respective capacity before 2040.

Globally, new coal power capacity of 350 GW is proposed, and 192 GW is under construction.

Given all of that, the IEA assesses that the world is not on track to phase out global coal consumption in line with the Paris Agreement.

The Markets Will Not Save Us

2022’s energy crisis has not helped in weening the world away from coal.

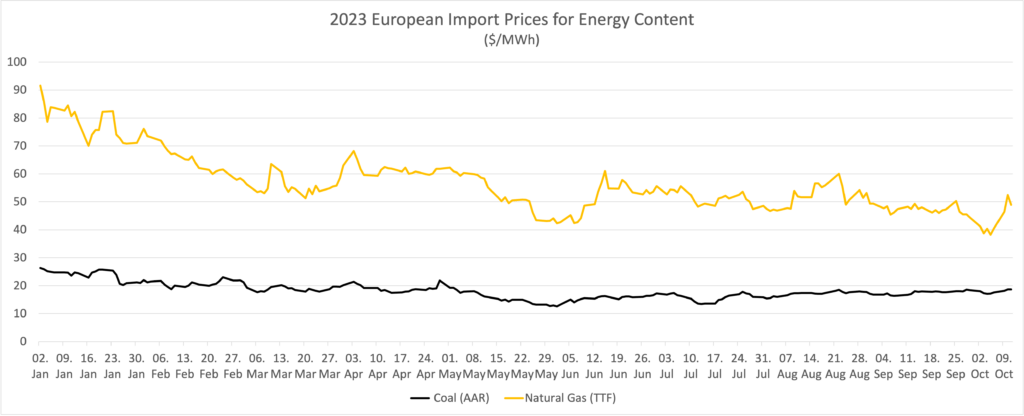

Clearly, the incredibly high gas prices played a role in turning lower-income countries back to coal to ensure security of supply and affordability.

In Pakistan, for example, competition with the EU resulted in hour-long blackouts when suppliers turned LNG tanks with already committed deliveries around to Europe.

Prices there were so high that it was more lucrative for firms to pay the contract penalty and sell in Europe than to live up to their previously agreed obligations.

There is no doubt that the 2022 price spike caused many Asian customers to return to coal as a pillar for their power generation.

This is a great setback for the energy transition of those countries, which assumed that natural gas could act as a conventional bridge until the full ramp-up of renewables.

(In a report from 2021, the IEA argued that this strategy would be endangered if gas prices were to rise above $10 per million British thermal units.

Needless to say, they rose far above that level one year later and still hover above $14 at time of writing.)

But even with the hot phase of the ’22 crisis receding into the past, prices are unlikely to bring customers back from coal.

Despite the return of gas prices to more moderate levels, they are still considerably higher on a per megawatt basis than for the same supply of coal.

They might come down further once new LNG supplies come online in 2025 to 2027.

But even a return to prices last seen at the end of 2021 would still bring gas back down to just about the same level as coal.

This is unlikely to incentivize a large-scale turn back to gas, assuming especially that the new infrastructure to burn coal will then be firmly in place.

One reaction to this might be to increase the costs of coal politically, i.e., through the introduction of carbon price.

But neither China’s nor Indonesia’s Emission Trading Systems – operational since 2021 and ’23 respectively – prevented the planned buildup in coal power plants.

And even if coal prices would increase above the level of gas, this might not necessarily decrease the level of coal consumed.

Instead, it might even lock in more future coal production.

This is because, due to the wide distribution of coal, most big consumers also have large resources within their own territory.

This is a significant difference to the more concentrated profile of natural gas.

Accordingly, when prices rise, many consumers can just increase their domestic production to bring them down again.

Countries like India and China already did this to deal with past price increases (see IEA (p.8)).

That mechanism significantly modifies the fuel competition between coal and gas:

If prices rise for gas, they can lead to fuel substitution, which might increase the use of coal.

If they rise for coal, they can lead to higher production, which could lock-in the future consumption of the resource.

Hence, it does not really matter if prices increase for gas or for coal, since coal might benefit in either case.

CCUS to the Rescue?

With gas not offering an alternative in the foreseeable future and the renewable transition seen as an ambitious goal, coal consumption seems inevitable in the foreseeable future.

To keep climate sustainability in reach, GHG emissions from that consumption needs to be kept as low as possible.

And this requires the large-scale application of Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage (CCUS).

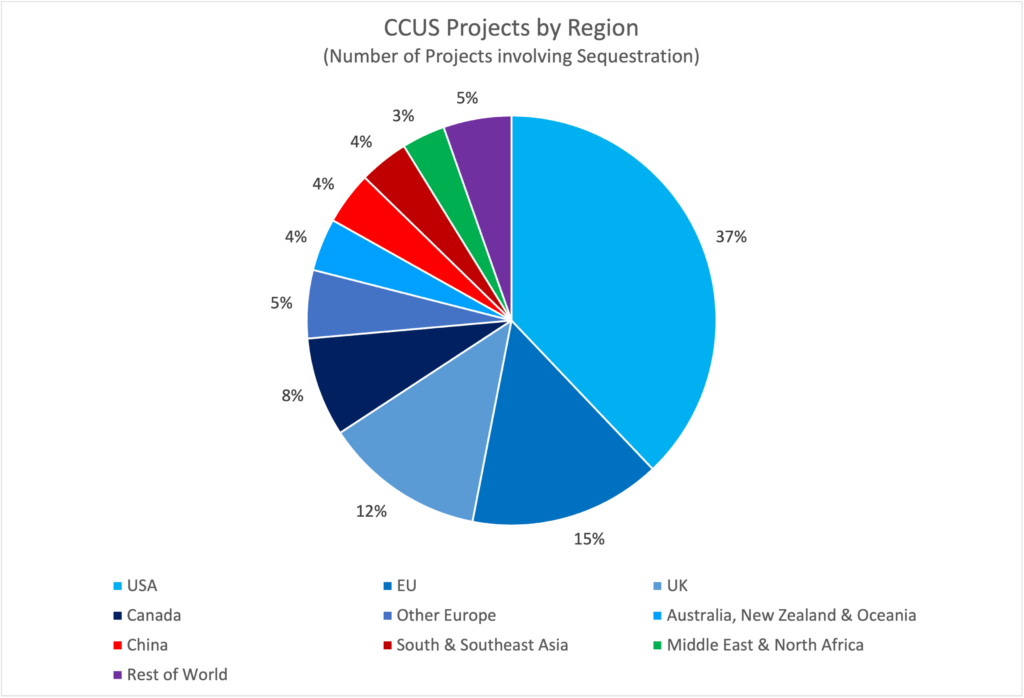

But with the vast amount of CCUS projects – both planned and operational – located in the West, a global asymmetry exists between the use of coal and the use of carbon sequestration.

Of the 459 sequestration projects currently under discussion or functional, 17 are situated in China and only two in India.

Neither of the Indian projects is currently operational, and none of them addresses emissions from power generation.

Similarly, none of the operational CCUS facilities in China reduces emissions from coal power generation, although three projects currently under construction will do that.

All other countries in East and Southeast Asia together have a combined number of 14 sequestration projects, ten of which are in Indonesia.

Not one of the Indonesian projects addresses coal power generation.

For comparison: The UK alone has 52 projects, while the US leads the pack with overall 155 planned or operational sequestration facilities.

The insufficient application of CCUS technology across Asia could be very bad news for the climate transition.

With coal power generation inevitably on the rise, lack of abatement would bring a significant increase in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Supporters of the energy transition might draw some hope from the fact that both India and China have net-zero objectives on the book – although neither country in the form of a binding law.

India’s President Narendra Modi announced on the Glasgow climate summit in 2021 that his country would become carbon neutral by 2070 and reduce emissions by 45% until 2030.

A bit more ambitiously, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced in 2020 that the People’s Republic would be carbon neutral by 2060 and have emissions peak before 2030.

With none of the two countries party to any international agreement to phase out the use of coal in power generation, political pressure for the adaption of CCUS can only emerge from these national objectives.

(Indonesia signed the UK’s Global Coal to Green Power Transition Statement, but only under the condition that it would not actually try to phase-out the use of unabated coal.

Neither China nor India signed the statement.

Indonesia, meanwhile, also does not have a set date for achieving carbon neutrality.)

Hydrogen to Clean up Steel Production

All this concerns mainly thermal coal, i.e., coal that is burned to generate electricity.

Beyond this stands the issue of metallurgical coal, which is the share of the commodity used in iron and steel making.

While being the less important driving force for global coal demand, metallurgical coal is still significant, amounting to 1.1 billion tons in 2021.

After declining in 2022, that demand is going to remain stable through 2025 at a level of around 1.08 billion tons.

While CCUS is the main option for decarbonizing thermal coal, climate sustainability in steel production increasingly focuses on green hydrogen.

In August this year, Tata Steel from India announced its intention to scale-up its hydrogen-based smelter technology after a successful test run that had started in April.

The company had already cancelled a decarbonization project using CCS in 2021, following its decision to focus on hydrogen instead.

This followed an earlier announcement by Rio Tinto and the world largest steelmaker China Baowu, to cooperate in the further decarbonization of steel production.

The companies aim to expand the use of China Baowu’s HyCrof technology that applies hydrogen to reduce CO2-emissions from the blast furnaces.

The Chinese firm reportedly also aims to build a net-zero steel plant in the Xinjiang Autonomous region.

In Europe, Swedish steelmaker SSAB plans to make production in its Luleå steel plant fully renewables-based between 2030 and 2040.

A first pilot project is already running.

While decarbonization for coal power generation rests on uncertain hopes for CCUS, the green hydrogen transition in steel production is slowly but surely picking up steam.