The August summit of the BRICS should have been a wake-up call for EU leaders.

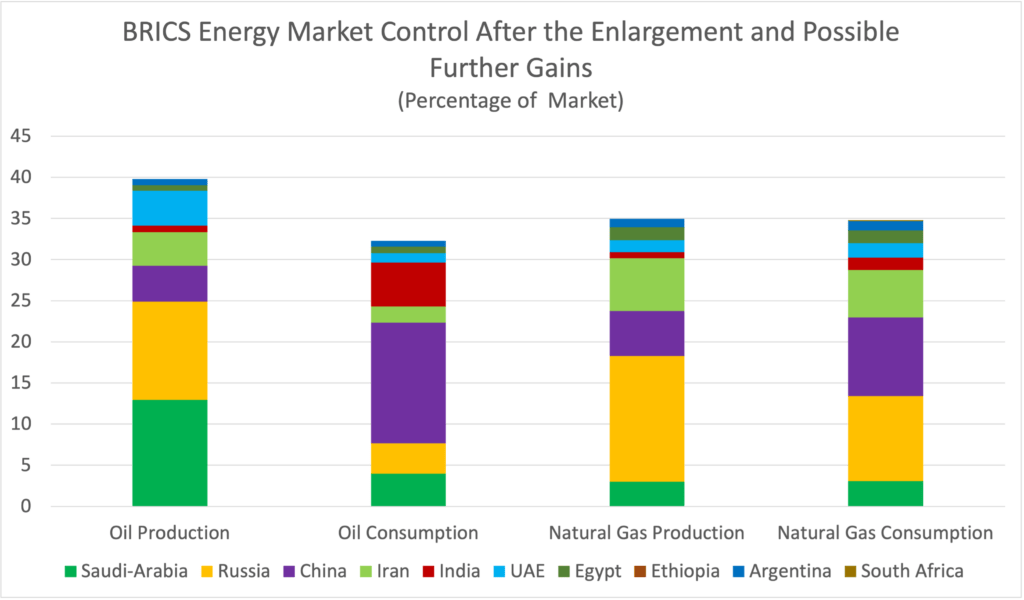

With the accession of Saudi-Arabia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates, among others, the group will have the potential to dominate energy commodity markets.

It now controls more than a third of global gas supply and demand, as well as almost 40% of worldwide oil production.

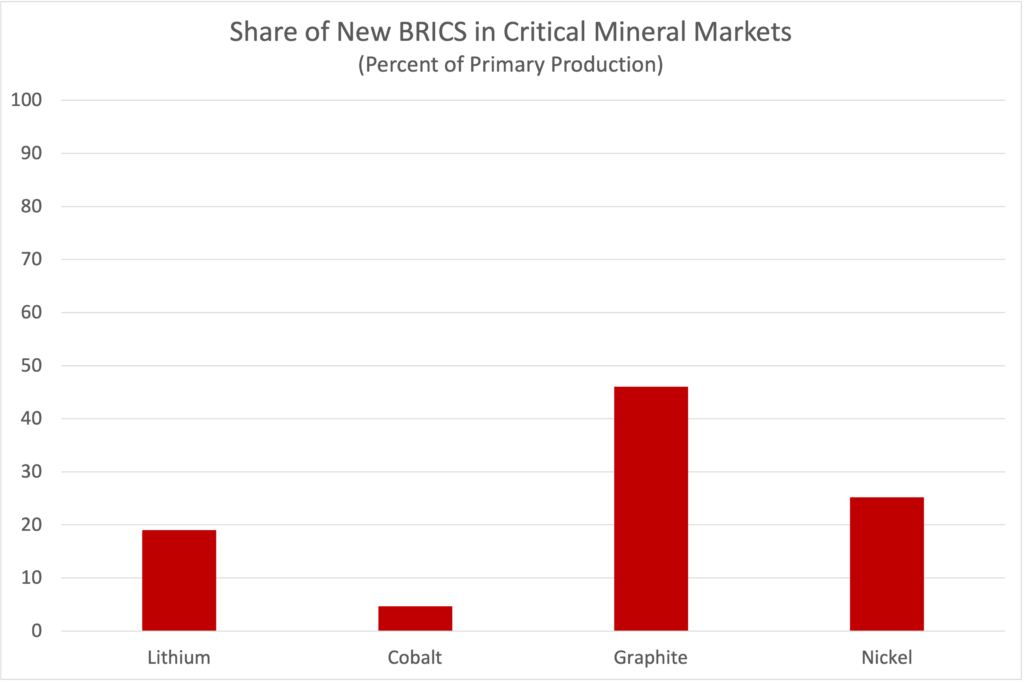

But the extended group also controls almost one fifth of global lithium reserves, more than one quarter of nickel reserves and no less than 46% of global graphite.

And the Democratic Republic of Congo, which holds 48% of worldwide cobalt reserves and generates more than 70% of global supplies, has already announced its interest in joining the new BRICS+.

While strong obstacles might very well prevent the group from acting like an outright cartel, increasing geopolitical tension could increase its incentives to resort to economic coercion.

Luckily, the EU has already started to strengthen its legal instruments against any attempts at economic blackmail.

But while the recent legislative changes – not fully supported by European companies – might be a welcome change from a security perspective, the EU is lagging behind in another field.

Perhaps ironically, this field is foreign trade, where the Commission should be especially well equipped to act.

But as recent developments around the free trade negotiations with Australia – a giant of all energy resources except oil – show, those key competences do not always translate smoothly into results.

Feta against the Energy Transition

Started in 2018, those negotiations almost came to an end in July 2023, when the two sides abruptly ended ongoing talks and decided to put the whole process on hold.

Even if the they later returned to the negotiation table, the whole process still throws a light on the specific European idiosyncrasies that could jeopardize the Union’s security of commodity supply.

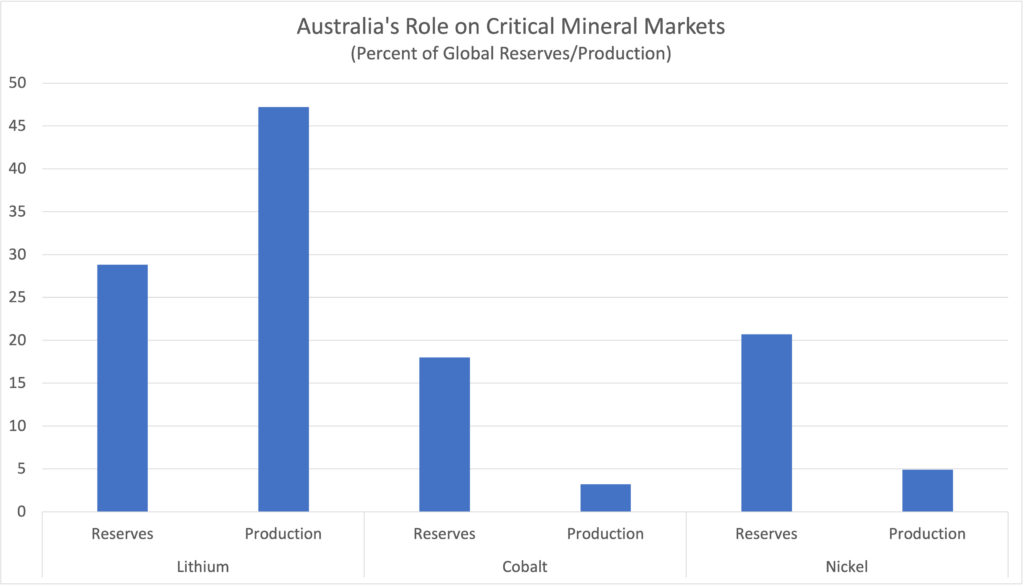

A simple look at the numbers gives an immediate impression to the great contribution Australia could make to achieving this objective.

According to the US Geological Survey’s Mineral Commodity Summary 2023, the country hold almost a quarter of global lithium reserves – although that might have come down due to a number of new finds, especially in the US.

It also holds 18% of global reserves in cobalt and 21% of global nickel reserves, making it a crucial supplier for three of the four most common materials needed in electric vehicle batteries.

Currently, Australia outperforms its potential as lithium supplier, where it provides more than half of global supplies.

It does not rank, however, among the top three producers of either cobalt or nickel, even though it has the second largest reserves for either material.

But Australia’s importance as an energy commodity supplier extends beyond critical minerals.

According to the IEA (p.18), the country also has 28% of global uranium resources, while it is also a leading LNG exporter in terms of capacity as well as actual deliveries.

More than that, due to its climate conditions, Australia could become a major exporter of green hydrogen – and has already delivered the world’s first hydrogen cargo by tanker to Japan.

As an integral part of the West, with close security ties to the US and strong political and cultural similarities with Europe, its resource wealth makes Australia a cornerstone for any democratic commodity strategy.

In fact, integrating this giant into a Western commodity sphere could be a strong counterweight towards the possible domination by the BRICS and the very real hegemony of China.

Clearly, concluding a Free Trade Agreement should be a priority for any European energy policy maker.

This, however, was not the approach of the Commission.

Instead, it chose to delay and potentially derail the possible Free Trade Agreement to pursue more pressing matters, including, among others, the specific nature and definition of Feta.

The point is that Australia produces a very popular version of the cheese – albeit made from cow’s milk – which is widely sold throughout the country and the whole of Southeast Asia.

According to EU regulations, however, only traditionally produced goat cheese from Greece itself might be called Feta.

But the Australians were having none of it.

And so, the parties adjourned.

Of course, negotiations were derailed not only be the dispute over the EU’s Geographical Indications (which also apply to Parmesan and Romano cheese, as well as other products, so this is not solely about Feta).

This dispute played out in the larger context of easier access for Australian dairy and meat products to the EU market, an access that the Commission has been reluctant to grant.

Why the Commission is reluctant to grant it is less clear, given that Europeans suffer from high food prices, which additional, tariff-free imports would probably bring down.

The Commission also objects to the Australian government’s policy to give its own companies and citizens preferential access to the country’s energy resources over foreign trade partners.

The government aims, for example, to retain a quarter of Australia’s LNG production within the country to keep energy prices for companies and households down.

The EU currently rejects this proposition, demanding instead equal access for both Australian and European consumers to all commodities.

Again, none of this is to imply that a Free Trade Agreement won’t be coming about – in fact, the Australians declared their intention to conclude it by the end of the year.

But the whole process serves as a timely reminder of the fact that energy and climate are not always the priority of the EU, all strategies and speeches notwithstanding.

Just look at how the EU allocates its money – perhaps the best indicator for actual priorities:

In the 2021 to 2027 Financial Framework, €22.8 bn of a €1.8 tn budget go to energy and climate action.

This compares to €350.4 bn for agricultural and maritime policies and still €73.1 bn for ‚European Public Administration‘.

This is not to say that energy is an afterthought to the EU.

But the bargaining tactics and priorities of the Commission certainly put its commitment to security of critical mineral supply into perspective.

Even if an Agreement would be concluded by December, the disruption and delay might still have caused relevant damage to the EU’s commodity position.

Better Trade Quickly

Australia’s energy sector needs investments not only to build up its own minerals refining and processing industry.

It also struggles with declining output of its major gas fields as well as with replacing its aging coal power plants – which requires gas to remain in the country as power source.

Beyond that, the country still has to invest significantly in mining to live up to its potential as a cobalt and nickel supplier.

All these things require urgent access to Foreign Direct Investments – investments that a Free Trade Agreement would certainly facilitate.

With only one LNG terminal fully funded until 2028 and the average ramp-up time for new mines being 15.7 years, Australia is at risk of foregoing its potential as a leading Western commodity supplier.

But delays not only endanger Australia’s commodity output.

They also strengthen the strategic position of the EU’s international competitors.

Australia’s mineral output currently goes overwhelmingly to China for further processing and manufacturing.

According to Australia’s Minister for Resources and Northern Australia, Madeleine King, around 96% of the country’s spodumene – a mineral that is rich in lithium – goes to China for refining.

And while Australia’s national government is eager to change that situation, the regional government of Western Australia until recently aimed to further deepen relations with the People’s Republic.

Although this has changed with the recent state elections, the fact remains that Australia’s distancing from its most important trade partner is not a given.

But the EU is competing not only with China.

In May this year, the US entered into a critical mineral and renewable energy partnership with Australia.

Beyond facilitating mutual direct investments in the energy and commodity sectors, the Climate, Critical Minerals and Clean Energy Transformation Compact foresees shared energy policies and objectives.

It enables the US government to treat Australian energy and commodity firms like American companies under the Defence Production Act, giving them access to the financial support from the US government.

Both countries also share a Free Trade Agreement since 2005 and cooperate in a rare earth partnership since 2020.

Bilateral cooperation has reached a level where Washington essentially subsumes Australia’s energy strategy and commodity riches into its domestic legislation and market.

Meanwhile, Australia and the EU continue to haggle about the naming of cheese.

The EU Regulates for Supply Security

When it comes to security of supply in critical minerals, the European Union is upping its regulatory game.

On October 3, the European Parliament passed a legislative resolution on the so-called Anti-Coercion Instrument.

Once passed, this regulation would allow the Commission to enact countermeasures against economic blackmail attempts by foreign countries.

These would have to rest on an implementing act passed by the European Council, which would, in turn, have to refer to a previous assessment by the Commission.

Those assessments include a statement by the country accused of economic coercion.

Concluding all these preliminary proceedings could take the better part of a year, according to the deadlines set out in the draft regulation.

Once the preliminaries have been observed, the Commission has the right to enter consultations with the (alleged) blackmailer.

These aim to get it to end the coercion and, if requested by the Council, repay all the damages resulting from it.

Only after these consultations have not led to a satisfying outcome after an unspecified, but ‚reasonable‘ period can the Commission take countermeasures – if these are both necessary and in the EU’s interest.

Those measures include, among others, the imposition of punitive tariffs or stricter restrictions on the import and export of specific goods.

Altogether, the whole process could take the actual imposition of countermeasures well into the second year after a coercive behavior has first been reported.

But it should be noted that important EU stakeholders – among them the German mechanic and plant engineering industry – would have preferred to have no anti-coercion instrument at all.

While the Anti-Coercion Instrument tries to stabilize the Union’s international reliance on critical minerals and associated production chains, the EU also aims to reduce this reliance as such.

In its Critical Raw Materials Act, the Union aims to increase its domestic extraction of key commodities by 2030 up to 10 % of annual consumption and its domestic recycling up to 15%.

The regulation also foresees that the Union will process 40% of its annual consumption in critical raw materials on its own territory and not import more than 65% of its annual consumption from a single country.

To achieve these objectives, the act introduces among other things a monitoring of supply chains as well as a duty for large companies to audit their procurement channels for critical minerals.

In a welcome addition of producer-friendly policies, the act also provides financial incentives and easier access to permissions for domestic mining and processing.