Over and over again, the old chestnut makes the round in Germany’s right wing circles:

The country’s energy supply would be much more affordable and safer if we just started to import gas from Russia again – preferably through the Nord Stream Pipeline.

With most of the pipeline currently defunct, supporters call for its urgent repair and an immediate restart of imports through the one (of four) remaining strands.

Strongly rejected by most of the political scene, that demand is one of the unifying factors between the country’s extreme right and extreme left.

Leaving aside for a minute the wisdom of getting your energy from a Mafia dictatorship with clear designs for domination over half of Europe:

How efficient are imports through the Nord Stream pipeline really?

Even if anything turned out great in Eastern Europe and cordial relations with Russia could be revived: Would it make sense to reactivate the pipeline?

Or is it just a geopolitical artifact, implemented by a power hungry, expansionary regime without regard for actual economics, and should be discarded for once and all?

That question has been debated to death and the answer to that question is going to surprise no-one with a remote interest in gas markets.

But since it rears its ugly head again and again in the debate (and high energy costs are an actual concern in Germany), perhaps some points deserve re-iteration.

Disregarding for now the question of the pipeline’s necessity from a purely volume-focused point of view:

Was it even the best option to increase imports from Russia if the gas to sustain that increase had been available?

The answer is, of course, an unambiguous no.

A simple look at the map should clarify this.

As any connoisseur of atlases knows, Northern Central Europe is overwhelmingly flat.

The highest onshore elevation between the gas fields that feed into North Stream and the town of Lubmin in Eastern Germany is no higher than 423 meters.

And that is right at the start of the system in the Russian region of Yamal.

Once you have passed that – and the perhaps the Suur Munamägi mountain in Estonia, with its majestic height of 318 meters (yes, I did a Google search for this article) – the rest of of track is pretty smooth sailing.

And you do not actually need to run your pipeline across the highest peaks in its course.

Clearly, if you want to build a new pipeline to expand your gas exports, that terrain provides the easiest option.

Why then opt for an underwater alternative – the most expensive terrain one could possibly route a pipeline through?

Length – the most important factor of pipeline cost – is not a concern.

With its overall length of 1,224 km, Nord Stream is only marginally shorter than the non-Russian part of the Yamal Pipeline that transports gas through Belarus and Poland (1,258 km).

Some authors argued that the water pressure would act as a natural compressor for the pipeline gas, reducing the costs for compressor stations.

But that is not a convincing point either.

Installation costs (CAPEX) are far higher for any pipeline than the operating costs (OPEX), that could be reduced by lower expenses for compressor stations.

(The Palgrave Handbook of International Energy Economics provides a good introduction to such questions.)

And within these installations costs, the pipeline itself is the most important factor.

With operating costs for compressor stations being a still relevant but secondary consideration, this argument for the undersea route does not stick.

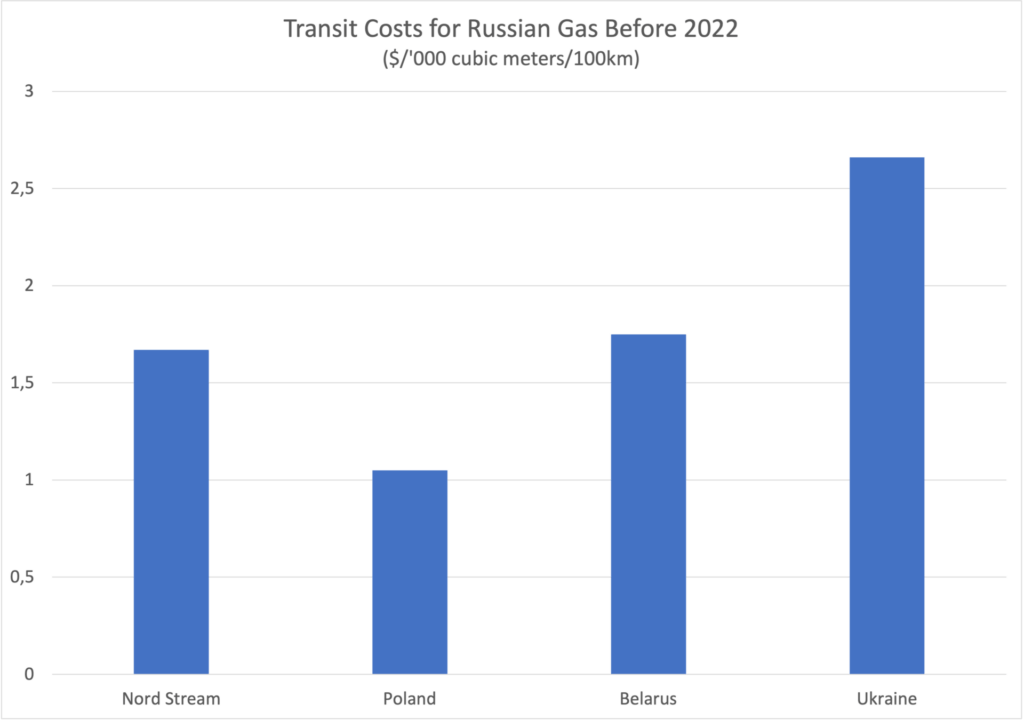

This shows in the transit fees payable for the different pipeline routes before 2022.

Admittedly, fees are higher for than Ukraine and Belarus than for the Nord Stream pipeline – $2.66 and $1.75 respectively, compared to $ 1.67.

But this is mainly a function of politics, not economics.

In Ukraine, the high transit fees resulted mainly from the country’s power over Russian gas exports.

With Russia continually trying to exert some form of hegemony over Ukraine, the resulting spiral of mutual blackmail attempts ramped the prices up to economically unjustified levels.

Relations for Belarus were less confrontational.

But here too, the higher transit fees reflected Russia’s desire to keep the country within its orbit.

This leaves Poland as the most important transit countries outside of Russia’s immediate zone of geopolitical interest – and under the sway of EU competition rules.

Here, transit prices stood at mere $1.05 / 1,000 cm / 100km.

That is $ 0.62 or about 37% less than its cost to transport the same amount of gas over the same distance through the Nord Stream pipeline.

What might sound like a trifle soon or later adds up to real money:

Moving the maximum possible capacity of the Yamal pipeline (33 billion cubic meters per year) through the Nord Stream system would have increased the annual fees by $ 25 million.

Reversely, expanding the Yamal pipeline to the capacity required for moving from Nord Stream would have reduced annual transport costs by $ 41 million.

There is no doubt: Routing a pipeline over the North European plain would have been by far the most cost effective way of getting gas from Russia to the EU.

There is, in fact, only one reason to lay a pipeline through the Baltic Sea instead:

To reduce the power of transit countries over Russian gas exports.

And this cannot concern Ukraine, since the Yamal pipeline already offered an option to circumvent that country and its fraught relations with Russia.

What then is the motive for Nord Stream?

The only perceivable answer is the immunization of German-Russian gas relations from any disturbance in relations between Russia and Poland or the Baltic states.

And since those countries would have to break EU law to cause such a disturbance in times of peace, the only possible cause could have been a more aggressive Russian stance against these countries.

So, in the end, the only reasonable conclusion is that the Russia hawks had it right the whole time:

Nord Stream’s objective was to increase the Putin regime’s leverage over Eastern Europe to facilitate future pressure tactics against Poland and the Baltic countries.

Strategically, the conclusion is clear:

Repairing and reactivating Nord Stream would only increase Russian relative power over Europe and endanger the future cohesion of the EU – even if the invasion of Ukraine comes to an end.

Economically, the only sensible way to re-activate gas imports from Russia would be through an expansion of the Yamal pipeline system to take over the volumes previously committed to Nord Stream.

That this can only come after a resolution to the war against Ukraine and following fundamental changes in Russia’s domestic setup should be obvious to anyone with a sincere interest in European security and liberty.

2. Russia was an Overall Reliable Source for Natural Gas

Behind the talk of reviving the Nord Stream pipeline lies the deeper notion that Russia has been, in fact a reliable supplier.

It is largely unclear how people arrive at that notion given that Russia unambiguously attempted to blackmail Germany into acquiescence through its dependence on gas.

It did so, firstly, by constantly reducing its deliveries to Europe throughout 2021.

While the old statement of the pro-Russian front that deliveries have always been stable still held for pipeline gas, the country systematically reduced its flexible auctions.

Through this instrument, Gazprom offered contracts over gas deliveries for different time frames starting with and for the same day up to contracts covering several years.

Over the course of 2021, Russia phased-out the more flexible contracts, leaving only the types with run-times of several years and start date some time in the future in place.

And in October, it ended even that.

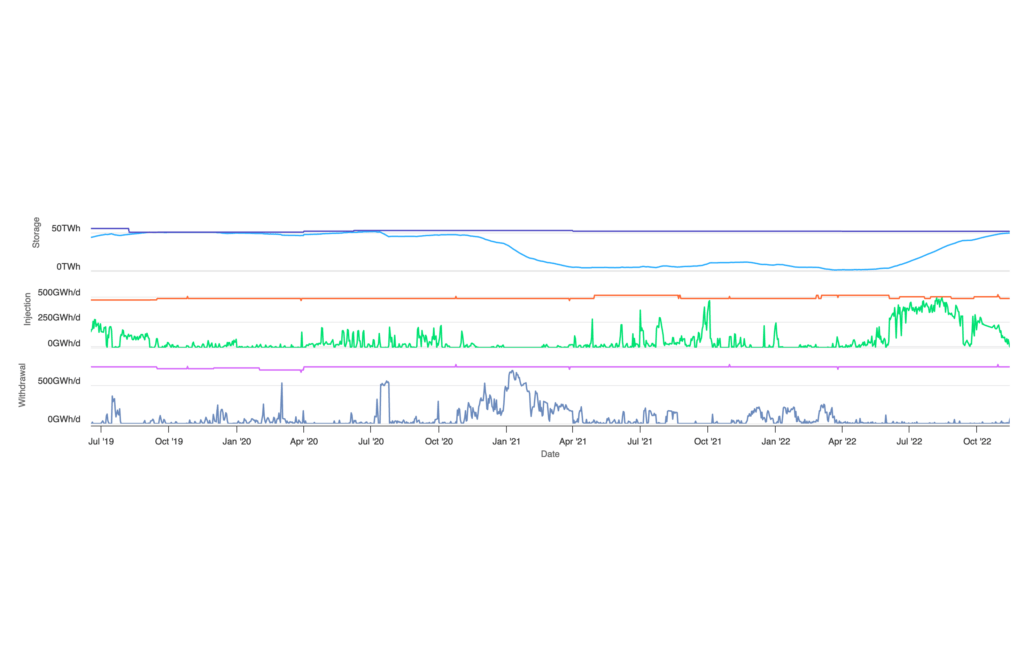

The scarcity caused by this was further exacerbated by the fact that Gazprom had systematically emptied the most important German gas storage facilities.

The facilities at Rheden and Jegum had been sold by the Merkel government to Russia – a decision that would lay the foundation for Gazprom’s blackmail attempts in 2022.

Usually, the Russian company would fill the facilities in the summer when gas consumption was low and draw down again during the heating period in winter.

Starting with 2020, Gazprom no longer filled the facilities, instead drawing them empty over the next years.

This process went largely unnoticed by the German government.

3. There Is a Real Risk That Russia Ends Its Gas Exports to Europe Completely

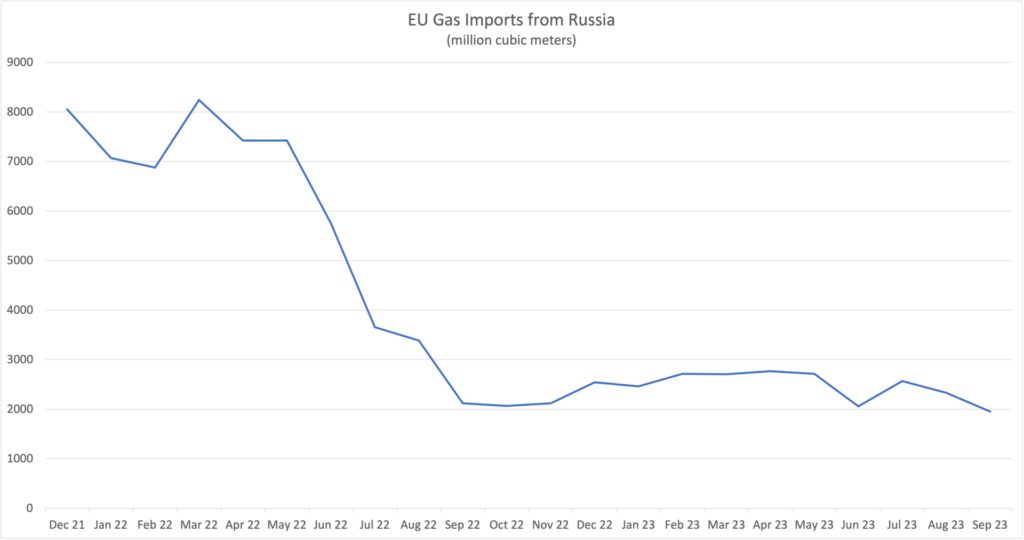

With natural gas not being subject to any official sanctions by the EU, deliveries are still ongoing.

However, since Nord Stream, Yamal and most of the Ukrainian pipelines are out of business for various reasons, all current deliveries go through the South Stream system, two small transition points in Slovakia and Poland or come as LNG.

These volumes have been drastically reduced since the start of the energy crisis.

But isn’t there a risk that Russia would cease its gas supplies to the EU completely?

And wouldn’t that endanger the continent’s security of supply and economic development both in the short and in the long term?

Let’s look at those concerns in turn.

First of all, while Russia might reduce pipeline deliveries to Europe, such a reduction would mainly hurt its own allies.

Even without any formal sanctions against Russian gas – pipeline or LNG – most countries with a critical attitude to Russia have long ended their gas imports from that country.

Even Germany – before the crisis criticized as being in thrall to Russian gas interest – has manged to ween itself completely off of imports from that country.

Others, like Bulgaria, have been cutoff by Russia itself as punishment for their negative reaction to Russia’s invasion in Ukraine.

According to Eurostat, more than three quarters of the remaining imports go through the Turk Stream pipeline to Bulgaria, from where it is forwarded to other countries, and Greece.

The remaining recipients of Russian gas reads mostly like a list of Russia’s supporters in the EU and wider Europe.

Most of the gas that enters Bulgaria, for example, is re-exported to Serbia, still one of Russia’s closest allies on the continent, even though it distances itself from the invasion.

(Despite its close relations with NATO and its interest in joining the EU, Serbia still has not levied sanctions against Russia.)

A large share of the remaining gas is forwarded to Romania, which has traditionally fraught relations with Russia, but again exports about a share of the gas to Hungary.

(That gas flows mainly through Serbia, with some additional volumes coming through Romania.

The Ukrainian pipeline system does not delivery gas to Hungary regularly since August 2022, and virtually none at all since January 2023.)

Hungary, of course, is perhaps the most prominent supporter of Russia within the EU, repeatedly delaying and watering down sanctions aimed at reducing the country’s war chest.

The Orban government justifies this position by pointing to the country’s dependence on Russian gas, oil and uranium supplies for its energy security.

Disrupting energy supplies to Hungary would directly undermine this rationale and significantly weaken Russia’s position within the EU.

The same holds – albeit less prominently – for Austria, that still receives some Russian gas through Slovakia.

While the country supports EU sanctions and is on the Putin regime’s list of hostile nations, it is also one of the first EU member states to explore a negotiated end to the invasion of Ukraine.

Federal Chancellor Karl Nehammer met Vladimir Putin in person in April 2022 to discuss an end to the war.

Overall, cutting the remaining pipeline supplies to the EU and wider Europe to exert geopolitical pressure is very likely to backfire.

Instead of strengthening Russia’s position in the EU it would overwhelmingly hurt its supporters and directly undermining the case for supporting Russia, namely preserving energy security.

What about LNG?

First if all, importing LNG from Russia still fills the country’s war chest and supports its illegal invasion of Ukraine.

But LNG imports can be more easily replaced than pipeline volumes and are, therefore, not as sensitive to energy security.

Also, Russia is unlikely to just forego those gas deliveries if it can redirect them to other buyers.

With gas prices in Asia frequently being higher than in Europe, Russian LNG exports would probably be sent to that region.

This could still mean higher prices in Europe, but it would keep the overall volume of gas available on global markets stable.

There would, therefore, be no increase in worldwide scarcity and any price increase in Europe would likely be moderate at best.

It should also be noted that 2024 is in all likelihood the last year in which global LNG supplies could possibly become scarce.

Between 2025 and 2027, massive new volumes of LNG are planned to enter the market, in all likelihood ending any danger of actual volume disruptions.

After that date, any end lack of Russian supplies could be easily replaced.

Finally, Russian LNG exports fall not under the same monopoly that Gazprom has for pipeline deliveries.

Many of them are conducted by Novatek, the country’s biggest private gas company, which is also the operator for Russia’s biggest planned new LNG terminal.

This still fills the Russian war chest through the export tariffs and taxes the Putin regime levies on LNG.

But it does not directly contribute to the wealth of a full state company, nor does it enrich Putin personally, if the rumors about his private holdings in Gazprom are true.

4. Growing LNG Imports Only Serve the Interests of US Fossil Fuel Companies

A final geopolitical argument is that all these LNG imports only serve to enrich US gas companies.

In this view, Berlin only turns away from all these affordable pipeline deliveries so that American gas millionaires can become richer at the expense of German households and businesses.

Certainly, companies make money if consumers buy with them instead of their competition.

And Europe’s need to draw LNG volumes away from Asian markets certainly increased global prices.

In the long run, however, it is unlikely that this would lead to long-term structural dividend for US oil and gas companies.

And it is virtually certain that the USA as a country would not profit from expanded LNG exports.

The reason for this is pretty simple:

The more interconnected markets become, the more the prices on those markets approximate each other.

As long as markets are largely disconnected, as is still the case for LNG, each market will develop its own price based on the local balance of supply and demand.

Those suppliers that can connect those two regions therefore can decide which of them to supply based on where they get the higher profits.

This arbitrage has been a key feature in global gas markets, favoring especially the US.

The fact is that the US produces far more natural gas than it consumes.

It also has, until now, only limited export capacities, meaning that much of the its domestically produced gas had to stay in the country.

This had a two-fold benefit for the US:

On the one hand it meant low gas prices on domestic markets, which also were largely insulated against global supply crises.

Even at the height of the 2022 disruption, domestic prices in the US never reached double digit figures, even when gas in Europe or Asia cost close to a hundred Dollar per mmbtu.

(Million British thermal units, the international reference term for natural gas trade.)

Under more normal conditions, Americans tend to pay between five and nine Dollars per mmbtu less than Europeans.

This not only makes live easier for households, but also gives American gas consuming companies a clear competitive advantage.

At the same time, US gas exporters are able to exploit arbitrage opportunities and sell their LNG to Asia and Europe at prices far exceeding those that they could get at home.

Increasing exports are likely to reduce both benefits to the US, simply because it would connect the American market more closely to the traditional importers.

Usually, such a growing interconnection leads to an approximation of prices, reducing the domestic cost advantage as well as opportunities for arbitrage.

A good example for this are prices in the EU and the UK, two legally independent but closely related markets.

Even though the UK has a significant domestic gas production, its prices are virtually in lockstep with those in continental Europe, with differences oscillating around ten Cent (US) per mmbtu.

Price differentials between the US and its customers might not decline this level.

But with export capacities increasing over the next years, those differentials are likely come down.

(Because more gas will leave the US, making it domestically more expensive, and reach the import markets, making it cheaper there.)

While increasing domestic prices might compensate compensate for some of the losses from the lack in arbitrage opportunities, they are unlikely to lead to overall higher profits.

And in any case, higher domestic prices would put a strain on American households and reduce its companies‘ competitive advantage.