Germany’s hydrogen strategy is ambitious to say the least.

By 2030, the country wants to have a production capacity for green hydrogen of 10 gigawatt (GW) for green hydrogen alone.

That contributes to the EU’s objective of producing 10 million tons of renewable hydrogen on its own soil and importing 10 million tons more on the global market.

That renewable hydrogen is going to have quiet a burden to carry.

Not only is it supposed to make steel production and other industrial processes carbon neutral and to replace fossil fuels in air travel and shipping.

Beyond that, it is also supposed to stabilize power grids, generate electricity, power fuel cells for hydrogen cars and trucks, and play a role in domestic heating.

But besides a largely aspirational green hydrogen map and the doubling of the objective for Germany’s production capacity in 2030, it is highly unclear where the actual volumes are going to come from.

Green Hydrogen – a Fraction of Less Than One Percent

A simple look at the numbers reveals how ambitious the idea of a green hydrogen economy really is.

According to the International Energy Agency’s recent hydrogen review, 95 million tons (Mt) have been consumed in 2022 – that is around one million tons more than in 2021.

What seems to be good news for the energy transition is, in fact, a sign for the resilience of the fossil fuel based system.

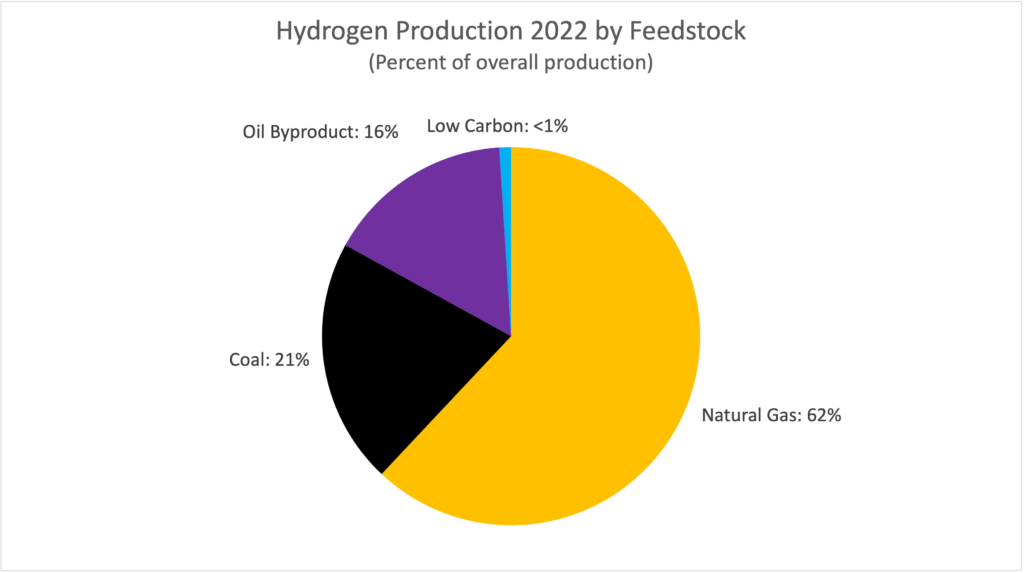

83% of all hydrogen worldwide is currently produced from fossil fuels without any emission abatement technologies.

(62% use natural gas as its feedstock and 21%, mainly in China, use coal.)

But this does not mean that the remaining 17% would be green hydrogen.

In fact, the overwhelming share of the remaining hydrogen is produced as a byproduct in oil refining – a technology that the energy transition is eager to phase out.

This leaves less than 1% of global hydrogen production in 2022 for low carbon sources.

Altogether, hydrogen produced with nuclear power (red), renewable energy (green) and from fossil fuels using CCUS technologies (blue) accounted for less than one million tons in 2022.

That amounts to less than 0.7% of global production.

The largest contribution within this group comes from blue hydrogen, i.e. hydrogen produced from abated fossil fuels.

Hydrogen produced from water electrolysis amounted to less than 100,000 tons – or around 0.07% of global production.

Mind you, that is hydrogen produced from electrolysis, which might use non-renewable electricity from the existing power mix.

With even that subgroup not necessarily green, we are talking about some part of 0.07% of global hydrogen production that is currently renewable.

In volume terms, this amounts to a contribution of somewhat less than 50,000 tons per year.

The German hydrogen strategy assumes that is possible to ramp that production up to a level where it is possible to run large parts of one of the most industrialized countries on the world with green hydrogen.

And that does not even consider the role that the stuff is supposed to play in the energy transition globally.

While not necessarily impossible, given sufficient funding and political support, this is certainly an ambitious goal – and not one that the world is currently on track to achieve.

Again according to the IEA, global low-carbon hydrogen production could reach 38 Mt by 2030, if all currently planned projects are actually implemented.

That would suffice to cover a bit more than a quarter of global hydrogen demand in a scenario where global energy systems become carbon neutral by mid-century.

But 55% of the new projects are still in the early stages of planning and might never realize.

Overall, achieving the kind of green hydrogen economy that the German strategy envisions will requires massive amounts of funding and sustained and strong political support.

But the most important obstacle consists in a completely different point that neither the German nor the European hydrogen strategy really address: Production cost.

Production Cost are the Strongest Obstacle For Green Hydrogen

The truth about green hydrogen is not only that it is exceedingly rare, but also that it is extremely expensive to make.

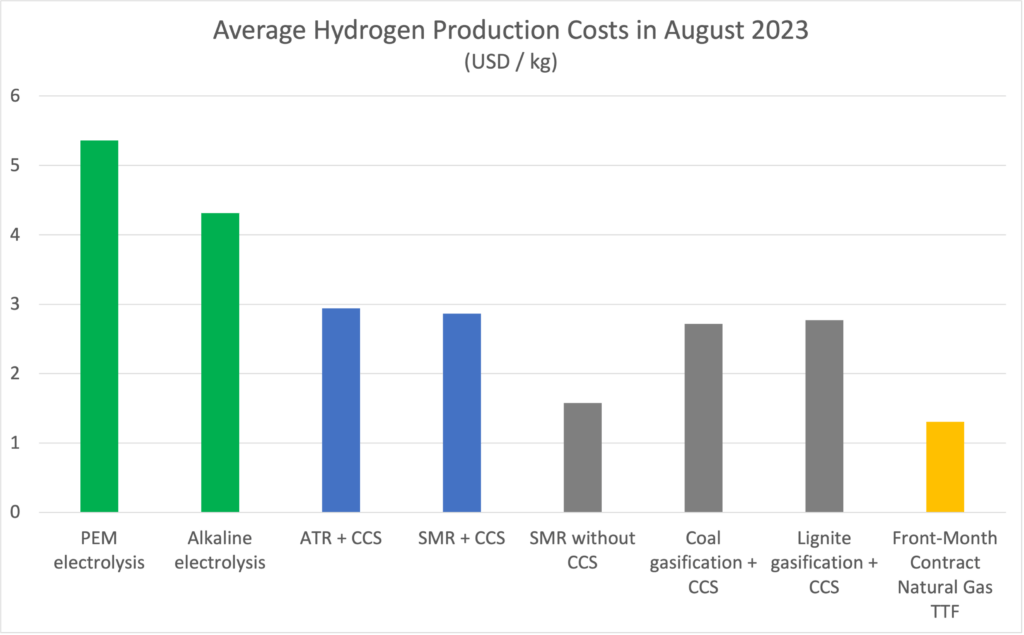

According to the Platts hydrogen price wall, it cost $5.36 to produce on kg of green hydrogen through Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolysis.

The corresponding cost for alkaline electrolysis stands at $4.31 per kg of hydrogen.

Compare that to the costs of hydrogen from unabated fossil fuels (grey hydrogen).

Even the most expensive outcome from that production method is still more affordable than the green variant with an average price tag of $2.77 per kg.

And there is simply no comparison to just using natural gas, which comes in at an average daily price of $1.30 per kg at the Title Transfer Facility in Amsterdam.

The only hydrogen that is anywhere close to competitive with a price of is the traditional version produced from natural gas without CCS.

With a price of $1.58 per kg, this is at least in the same ballpark as natural gas.

(Note however, that averages for hydrogen reflect average production costs over different regions, while the natural gas average represents daily costs at the TTF.

Actual price differences are, therefore, likely to be even more skewed in favor of natural gas.)

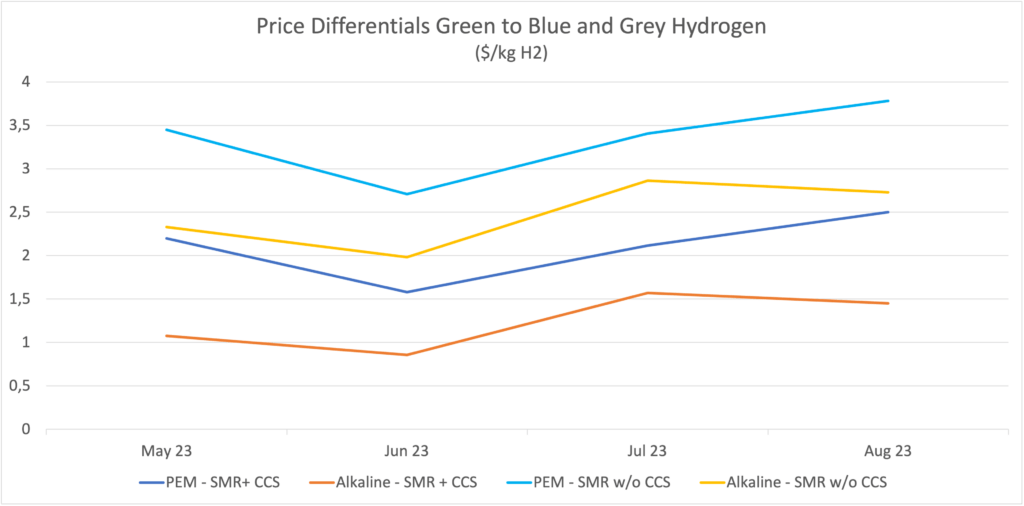

At least in the short term, those cost differences did in fact increase.

Price differences for all versions of electrolysis compared to abated or unabated Steam Methane Reforming – the predominant production method for blue and grey hydrogen – were slightly higher in August 2023, than in May of this year.

For PEM electrolysis, this difference was no less than $3,78 per kg of hydrogen produced – exactly 33 Cents more than in May.

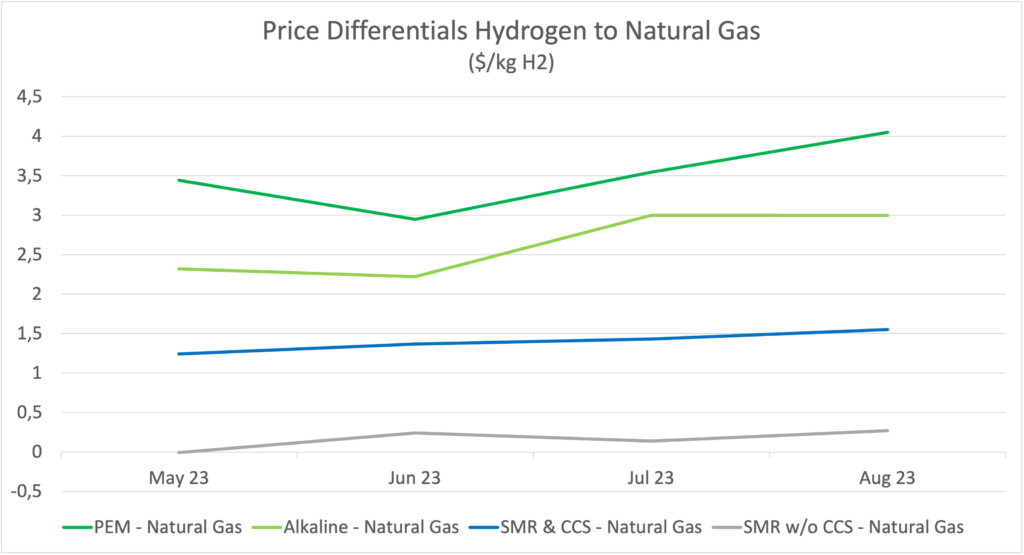

Price differentials and their growth are even more pronounced in comparison with natural gas.

Producing one kilogram of hydrogen from PEM electrolysis cost $4.05 more than buying a kg of natural gas at the TTF – which includes other cost elements besides production.

That difference has increased by $1.6 since May and might increase further since gas prices are likely to fall faster than the production costs for green hydrogen.

Compare that to the price differential for grey hydrogen, which comes in at $0.27 in August and was even negative in May!

(Again, the comparison here is between global average production costs over different regions regions for hydrogen and daily average buying price for front-month futures at the TTF.)

Sooner or later, those differentials are going to ad up to real money.

The German steel industry estimates that it would need 2.2 Mt of green hydrogen to become fully climate neutral by 2050.

Depending on production method and assuming that price differentials remain the same, that would amount to additional costs of between $6.6 and $8.9 billion compared to just using natural gas.

Compared to grey hydrogen, industry-wide annual additional cost would come in at between $60 bn and $8.3 bn.

Blue Hydrogen Offers a Feasible Mitigation Strategy

Many observers, especially in Germany, argue that only green hydrogen may be used in the future energy transition.

This excludes not only fossil fuels and fossil fuel-based hydrogen, but also other versions of the low-carbon variant, too.

(A major bone of contention between purist Germans and France that wants to – and should – market its nuclear power-generated hydrogen as a solution to the climate crisis.)

But besides the focus on green and the debate over red hydrogen lies of course the blue variant – hydrogen produced from abated fossil fuels.

At least if you believe data from the IEA’s report on the emission intensities of different types of hydrogen, there are clear advantages to using processes with abated fossil fuels.

(These advantages become even more pronounced if you use data from the Hydrogen Council, which few environmentalists are likely to do.)

Besides providing the overwhelming share of low-carbon hydrogen that is actually currently available, blue hydrogen does, according the IEA, bridge the objectives of economic feasibility and ecologic sustainability.

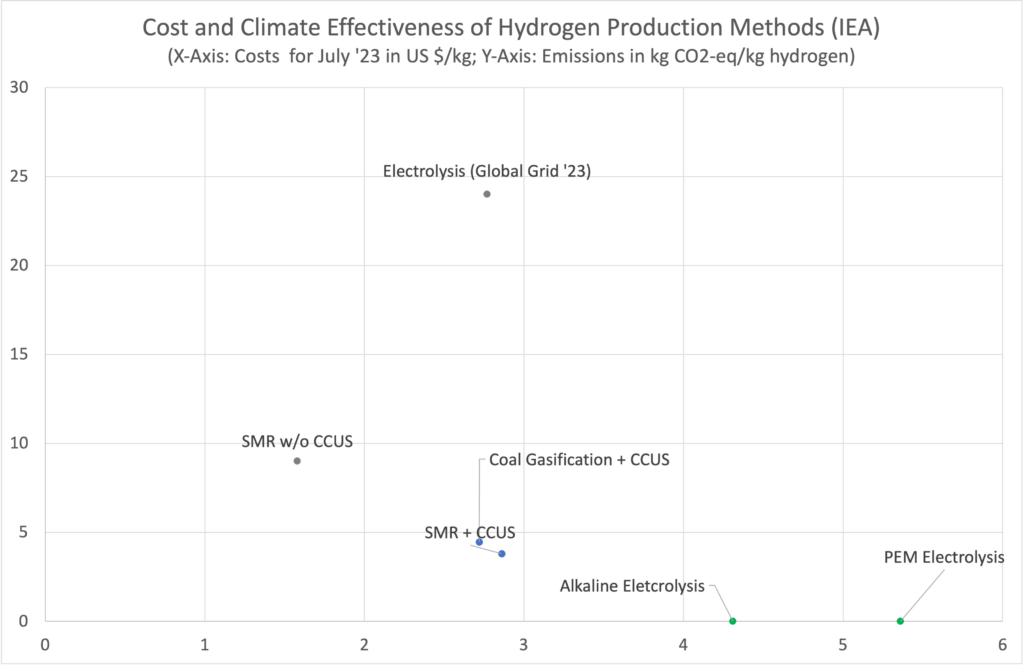

Combining Platts‘ price data with the Agency’s data on emissions intensities quickly gives an impression of blue hydrogen’s key position.

With an average production cost of $2.86 per kg and an emission intensity of 3.8 kg CO2 equivalent per kg of hydrogen, blue hydrogen is both on the affordable and the sustainable side of the spectrum.

As such, it could offer at least a bridging technology until the costs for green hydrogen come down considerably, or even a structural part of a future low-carbon hydrogen economy.

The IEA and other proponents of blue hydrogen assume that CCUS captures around 90% of the greenhouse gases from hydrogen production.

This might be a tall order for a technology that not always lives up to expectations.

But even a very critical 2021 study of blue hydrogen’s potential argues that it is more climate effective than the currently predominant grey production methods – albeit not to the extent its supporters envision.

In their analysis, Robert W. Howarth and Marc Z. Jacobson found that blue hydrogen emits only 9 to 12% greenhouse gases less than grey hydrogen.

This results not only from a more critical attitude towards CCUS.

The authors also consider the fugitive methane emissions from transporting the natural gas as feedstock and using it to generate the electricity for the production process.

Based on this, they argue that blue hydrogen is even worse from a climate perspective than just burning natural gas directly.

Results of this study have been quoted as evidence that blue hydrogen cannot play a role in climate-friendly energy transition.

But while the IEA and others might be to positive on abated production methods, this study might have been too strict.

It assumes, for example, that the electricity for the SMR process is generated by burning natural gas, which is not necessarily the case.

The study also does not take into account the possible ways to reduce methane leaks in transportation, which would further bring emissions down.

Hence, even without diving into the debate on the assumptions and models that went into the 2021 study, it is clear that its results on the associated GHG emissions are certainly on the higher side of the probable spectrum.

And even these results are still more climate-friendly than the corresponding outcome for grey hydrogen.

Overall, blue hydrogen makes a clear climate contribution, constitutes the majority of current low-carbon hydrogen and has a significant cost advantage over green hydrogen.

Especially given the right measures to reduce methane emissions, it offers a good compromise between the objectives of ecologic sustainability, economic affordability and social equability.

Green Hydrogen Production Costs Must Come Down

The cost factor, however, is crucial not only to protect energy intensive industries and low-income households from still further price shocks.

(Note that German industrial production is still below the level of 2020, even without a further increase in energy prices.)

Beyond those concerns – and especially social equability deserves more consideration in the German debate – cheaper hydrogen is absolutely key to the energy transition itself.

As long as hydrogen remains more expensive than natural gas, it will never become the fuel of choice for companies and households – all climate concerns notwithstanding.

And, barring any new geopolitical crisis, natural gas is not only not going to become more expensive over the next couple of years; it is far more likely to become cheaper.

With large LNG additions coming online in the US and Qatar from 2025 to 2027, increasing gas supply is likely to bring prices down, perhaps even back to prewar levels.

This will further skew the already strong cost asymmetry in favor of natural gas.

Market forces will not make natural gas more expensive than hydrogen.

The German government’s solution to this challenge consists mainly in a combination of legal prescriptions and an attempt to make gas more expensive through the Emission Trading System.

The government’s hydrogen strategy has less to say on making hydrogen cheaper, beyond a general hope that increasing demand will bring unit costs down in the long run.

Not only does this approach leave the question open of what happens in the meantime when natural gas is already more expensive and hydrogen costs have not yet come down.

It also introduces a significant risk of backpedaling into the overall German transition strategy.

The notion that any future government will stick with higher gas prices once these have a widely perceivable impact on living standards and economic well-being seems fanciful.

Even the current traffic light coalition, which is the most climate-friendly government Germany can realistically expect, has weakened and postponed the planned price increases for emission certificates.

It is unlikely that a future, and in all likelihood less climate-friendly, government is going to stick with a policy that means higher expenses and lower living standards for its voters.

The fact that natural gas is going to be integrated into the EU-wide Emission Trading Scheme is no obstacle to its future removal.

As the conflict over the Internal Combustion Engine proved, Germany is very able to assert its will on the European level when it wants to roll-back already agreed-upon climate rules.

And if the anti-EU, pro-fossil party AfD should consolidate its current standing in the polls, a softening and reversal of expensive, living-standard reducing policies becomes even more likely.

Supporters of the energy transition should, therefore, not put their hope in an instrument that rests solely on political fiat, negatively impacts the live of voters, and has absolutely no basis in an underlying economic reality.

There is only one way to make sure that low-carbon hydrogen becomes a key pillar of a future climate-positive energy system and that is to make green hydrogen cheaper.

Then, with some support from a moderate carbon price, the turn towards clean hydrogen might have future independent from political developments.

More Political Support is Needed

This, however, is unlikely to come about without significant political support.

The IEA (p. 6) estimates that the costs for green hydrogen could come down to $1.3 to 4.5 per kg by 2030.

This is a significant decline from the current $3.4 to 5.4 per kg.

The main drivers for this are going to be the expansion of electrolyser capacity and the decline in the cost for renewables.

The lower end of the future cost spectrum would be realistically achievable in regions with good access to affordable renewables.

In so far, the German and EU hydrogen strategies with their focus on supply and demand expansion, embedded in an overall strong growth for renewable power, is on the right track.

But a price tag of $1.3 to 4.5 per kg would still come in at $39 to 145 per megawatt hour (MWh).

Only the lower end of this would be competitive with the sales price of natural gas at the TTF – and this includes other costs beyond production.

True, natural gas was more expensive than this during the 2022 crisis and still costs more than $39 per MWh at time of writing.

But these extraordinary price levels are unlikely to persist after the new LNG terminals in the US and Qatar go online in 2025 to 2028.

If gas prices to their pre-crisis levels in the second half of the decade, any hopes of green hydrogen becoming competitive on market dynamics alone might proof misguided.

Hence, to avoid the risk of political u-turns, additional measures must be taken to reduce the costs of green hydrogen across the whole value chain.

A first step would be to reform the tariffs on hydrogen imports, which currently stand at 3.7% across the board.

Reforming the EU tariff system to reflect the CO2 content of different hydrogen types could be done through a relatively simple amendment of the combined nomenclature.

Beyond that, tax incentives need to be extended to every step of the value chain for low-carbon hydrogen.

In the US, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) grants tax incentives for low carbon hydrogen of up to $3 per kg, almost as much as the cost differential between green and grey hydrogen.

In Germany, hydrogen does not fall under the Energy Tax Law.

But an incentive similar to the one in the IRA could be granted to other cost dimensions of low-carbon hydrogen production.

The newly revised EU Energy Taxation Directive, if passed, will extend the lowest possible minimum taxation rate to low-carbon hydrogen for a provisional period of ten years.

This should be made permanent.

Tax incentives should also apply to the capital and operational expenditures for low-carbon hydrogen production, since it is production cost, not direct taxation, that makes green hydrogen uncompetitive.

Overall, Germany’s and the EU’s hydrogen plans are extremely ambitious.

Many objectives, like a crucial role for hydrogen in individual transportation or domestic heating, are unlikely to ever realize.

But working energy transition strategy that still aims to keep industry alive and living standards stable cannot solely consist in making fossil fuels consistently more expensive.

When it comes to green hydrogen, the key strategic objective is clear:

Producing it must become way cheaper.