Even in field as full of contested questions as the energy transition, the future of oil still sticks out as an especially controversial topic.

For some, oil is the very incarnation of an environment destroying fossil age, being pushed down the throat of a dying humanity by unscrupulous special interests.

For others, it is still the one best energy source civilization can rely on, the highly efficient and well tested driving force of human progress.

There seems to be little common ground or possibility for compromise between these groups.

But simply looking at the numbers, it seems that the proponents of oil are going to get their way.

Not only are there no comprehensive plans to end the exploration for or production of oil – in fact, most producers plan to put more of the stuff on the market.

And oil companies that already had been in place plans to diversify into renewables are rolling them back, putting them on hold, or relegating them to the sidelines.

All medium-term production cuts aside: Oil supply is going to grow over the next years.

This might not be enough to prevent any future supply gap, but it is certainly sufficient to allow for a healthy – or fatal, depending on your point of view – inflow of additional oil volumes.

Perhaps more importantly, the expanding production portfolio signals the industry’s strong optimism about the future of oil demand.

After all, you do not invest in a commodity that you think you will be unable to sell.

And herein lies the crux of future oil market development:

Not a single baseline scenario foresees oil demand to go down significantly by 2050.

All scenarios that foresee such a reduction are usually goal-driven, i.e. they strive to find the best way towards global carbon-neutrality by 2050.

Not a single projection that looks upon the policies actually in place foresees a significant decline in oil consumption.

And even scenarios that consider policies that are announced, but not yet implemented do not foresee a net-zero development of oil markets.

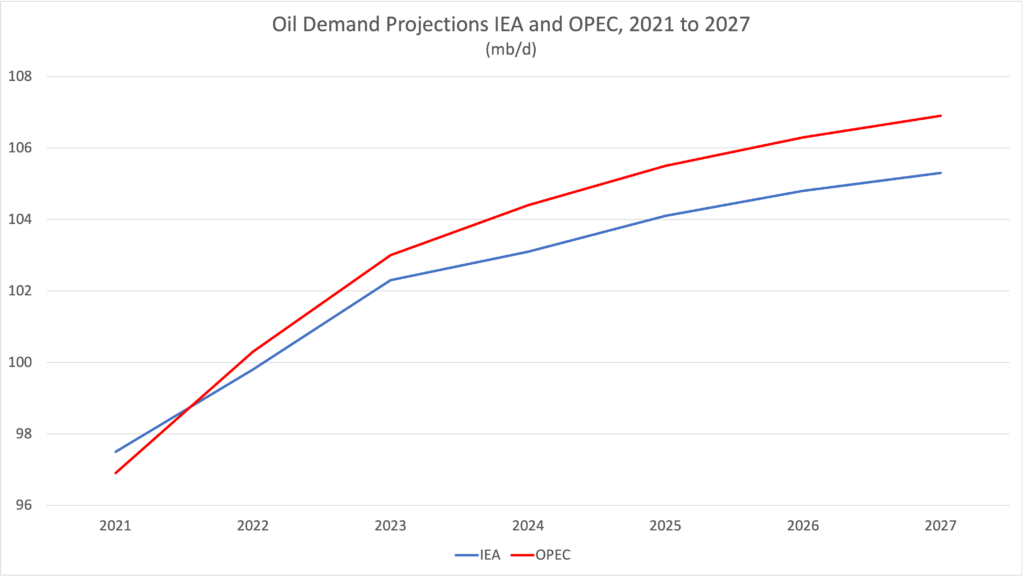

Instead, several scenarios expect a substantial increase in demand, even compared to the record values reached in 2023.

So, with supply capacity expanding and demand probably remaining stable, the future of oil seems safe and sound.

Let’s look at both aspects in more detail.

Divesting No More

Nowhere is the struggle over the future of oil more dramatic than in the supply from Western companies.

Be it anti-oil activists hijacking shareholder meetings to express their anger in song, or riot police firing tear gas at climate activist in front the building:

Few energy policy debates are as eventful as the conflict over oil production by European companies.

But more important are the law suits the Stop-(Western-)Oil movement pursues, and the resolutions it supports at the oil majors‘ shareholder meetings.

It were these instruments – intermittently supported by mainstream investors like Blackrock or the UK’s Legal & General – that accounted for the actual successes of the disinvestment movement.

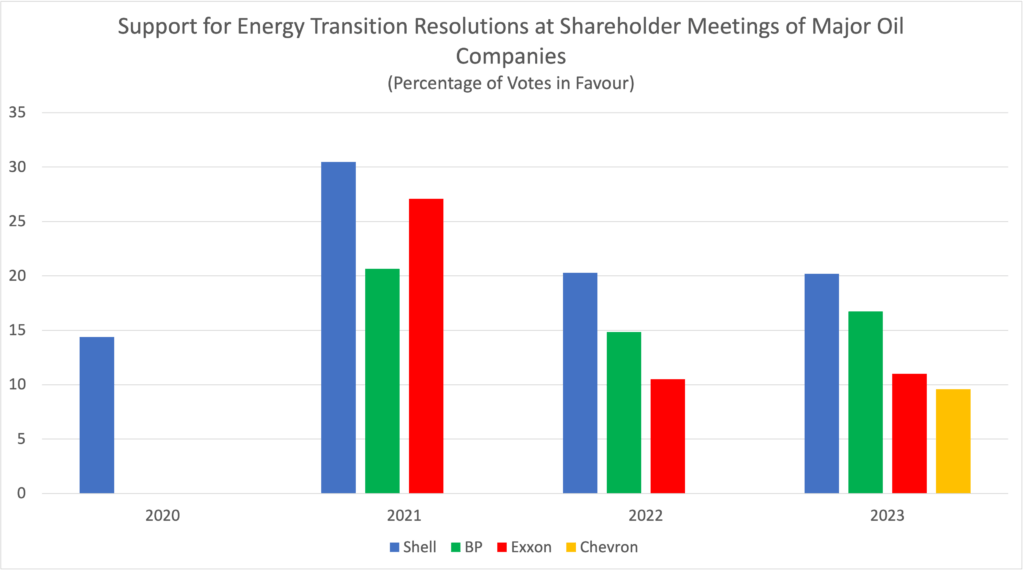

Especially in May 2021, that movement seemed to be on the verge of a breakthrough.

In that month, the District Court of The Hague decided that Shell’s climate plan had to account for the so-called scope 3 emissions.

Those are the emissions that result from the use of oil products by the final customer.

Therefore, to achieve its court ordered reduction objective of 45% by 2031, the company was forced to invest in low-carbon energy sources and diversify away from oil.

The same month, activist hedge fund Engine No.1 managed to get three of its representative elected to the board of Exxon.

Still in May 2021, shareholders of Chevron voted for a proposal to cut the company’s own Scope 3 emissions.

All of that came in top of the seminal International Energy Agency’s Net Zero report.

In this, the Agency stated that the world would need no more investments in oil and gas if it were to embark on actual course towards carbon neutrality by 2050.

(This has sometimes erroneously been reported as a call to stop investments in oil and gas.)

Suddenly, the divestment movement had the support of American oil majors and a (supposedly) major court order in the bag.

What seemed to be its breakthrough moment, however, did not last long.

Already in early 2022, the UK High Court decided that scope 3 emissions need not be considered in the environmental impact assessments of oil and gas projects.

Although the climate group Friends of the Earth appealed against that decision, it was subsequently upheld.

(Two similar cases in South Korea (p. 39) led to the same outcome.)

Other cases confirmed that oil and gas companies only need to consider their direct emissions in environmental impact assessments.

Those cases meant that the inclusion of scope 3 emissions was rejected even by a jurisdiction as close to continental Europe as the UK.

It became clear that the decision in The Hague would have very limited impact at best.

And with the divestment movement’s judicial progress stalled, the effects of the 2022 energy crisis brought its successes on the shareholder side crashing down.

What felt like an existential challenge to many households and companies across the world, looked like an unstoppable rally to oil and gas producers.

With especially gas prices climbing to hitherto undreamed of highs, fossil companies were busy raking in one record profit after the other.

The conclusion for the companies was clear:

Put a break on all this transition talk and get back to business.

Transition plans where quickly abandoned, as the managers that had pursued them left and their positions were eliminated.

Support for the anti-oil resolutions fell with each consecutive shareholder meeting.

Companies meanwhile refocused on what they saw as their core activity: Getting oil and gas out of the ground and towards their customers.

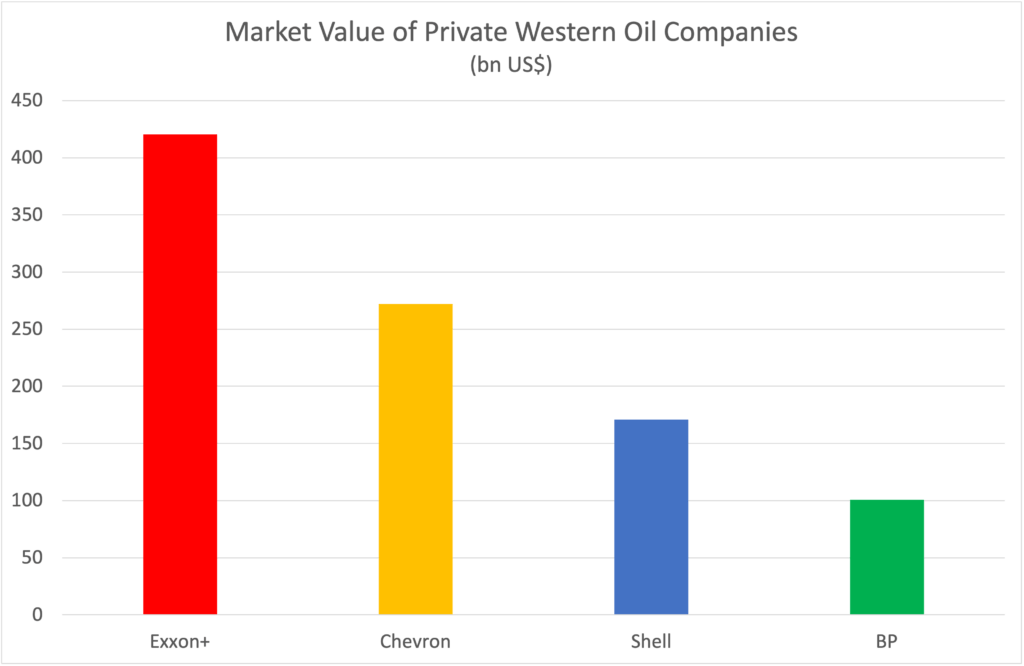

And financial markets essentially agreed with them.

With a visible inverse relation between company value and transition commitment, the message to oil and gas companies was unambiguous:

Focus on oil and gas if you want to grow big.

Focus on the energy transition if you want to lose market value.

(It should be noted that the most valuable oil company by far is state-owned Saudi Aramco with a valuation of over $ 2 trillion.)

So, with the judicial strand of the divestment movement stalled and financial incentives firmly set against the energy transition, oil companies returned to what they did best:

Producing more oil.

The Companies Invest in Oil

Take Shell, for example, a company that presumably still aims to become ‚a net-zero energy business by 2050‘.

The company is currently exploring for oil in, among others, Mauretania, Brazil and Kazakhstan.

With its share in the large-scale Prelude and LNG Canada projects, it is also a key player in the ongoing expansion of global natural gas supply.

BP, with a net-zero objective for 2050 or earlier, is currently constructing eight new major projects across five continents.

Together, these projects will bring 280,000 barrels of oil to the market as of 2025.

Meanwhile, Exxon is the main driving force behind the oil boom in Guyana.

As recently as 2019, that country did not produce a single drop of oil.

Now, its output stands at 380,000 barrels per day and is planned to grow to 1.2 mb/d by 2027.

That expansion is organized by a consortium led by Exxon (45%) and also including Hess (30%) and the Chinese National Offshore Oil Corporation (15%).

These are just some snapshots from an industry that is generally eager to bring more oil to the market.

Besides these new exploration projects, the companies‘ mergers and acquisition activities show just how bullish they are on the future of their market.

In one of the biggest takeovers of the recent years, Chevron acquired (formerly) independent oil company Hess for $53 bn.

This not only increased Chevron’s assets in the US shale industry.

It also made the firm a participant in the massive Guyana oil boom.

Before that, the company already extended its reach in the US shale sector through the acquisition of PDC Energy and Noble Energy.

All of this brings Chevron’s total oil and gas output to 3.7 mb/d (almost 4% of global demand), 1.3 mb/d of which are from shale.

At the same time, Exxon’s $ 59.5 bn acquisition of Pioneer Natural Resources made it „the biggest producer in the largest US oil field„.

Together, the combined companies now bring 2 mb/d of oil equivalent to the market.

Markets are Likely to Remain Tight

Despite all these activities, global investment in oil exploration and production stands at only $ 579 billion in 2023.

This is only slightly higher than the 2015 to 2022 average ($ 521 billion per year).

And the share of successful exploration projects diminished significantly, with the first half 2023 yielding only 2.6 billion new barrels of oil equivalent.

This amounts to a decline by 42% compared to the same time in 2022.

Producers are in fact concerned that investment levels might be to low to satisfy medium-term demand.

They fear that, with policies disincentivizing investments in exploration and production, funding might be permanently below what is needed for market stability.

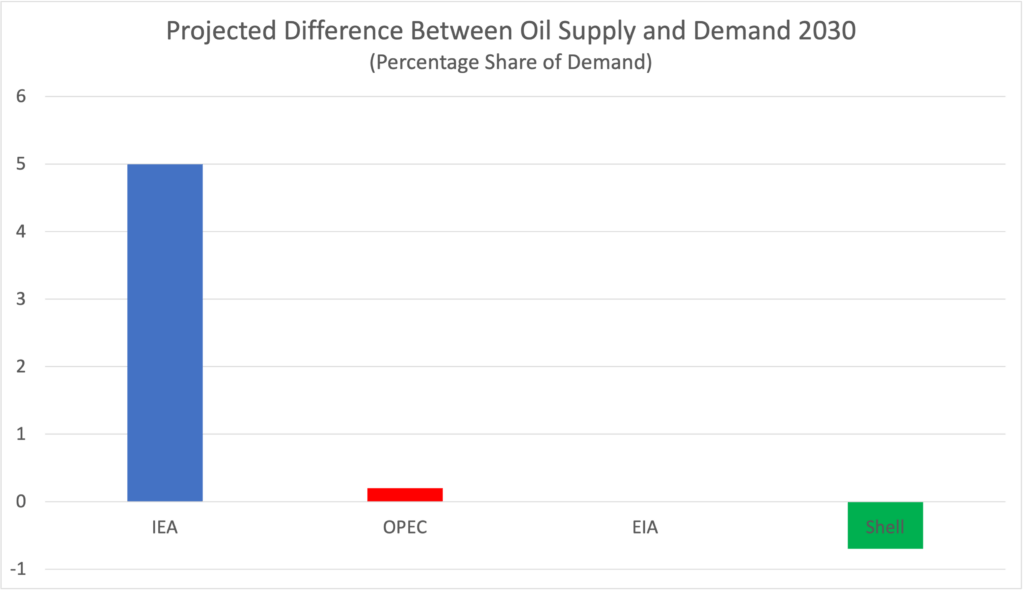

Most scenarios actually predict that supply will just be enough to cover demand in the foreseeable future.

The IEA’s baseline scenario even projects a relevant oversupply of five percent of expected demand in that year.

(The biggest deficit of 0,7% of expected demand coming from Shell’s baseline ‚Archipelagos‘ scenario.)

Hence, what supporters of the energy transition see as an investment rush into a damaging oversupply, might in fact just be enough to cover requirements.

And any significant interruption is likely to throw the market out of balance.

The Global South Joins the Party

As already mentioned, Guyana alone plans to bring its current 380,000 barrels per day up to 1.2 million by 2027.

After that, Namibia looks like the next frontier in the global rush for oil.

Until now, the country did not produce any oil.

But it became a top candidate for the next bonanza when a consortium led by Total and Shell found no less than 11 billion barrel of oil reserves in its maritime economic zone.

While not anywhere close to even mid-sized OPEC members like Libya or Nigeria, these reserves put Namibia ahead of countries like Norway and Oman.

Together with the 24.6 bn cubic meters of natural gas the consortium found as well, Namibia is ramping up to become a major fossil fuel supplier.

Its government expects to the see the first production by 2030 – which is around the time when most scenarios predict global oil demand to reach its zenith.

More established producers are not to be outdone.

Kuwait, for example, aims to increase its production to 4 mb/d in 2035, up by 1.3 mb/d from today’s output.

And in 2030, the country wants to produce 3.15 mb/d instead of the 2.7 it does now.

Meanwhile, Saudi-Arabia wants to add a further million barrel per day to its production capacity by 2027.

Despite all homilies about ’neoliberal extractivism‘ and the ‚exploitation of the Global South‘, it is that very Global South that is a major driver of future oil production.

Demand: Stable in the Foreseeable Future

Oil demand, meanwhile, is likely to remain stable over the next couple of decades.

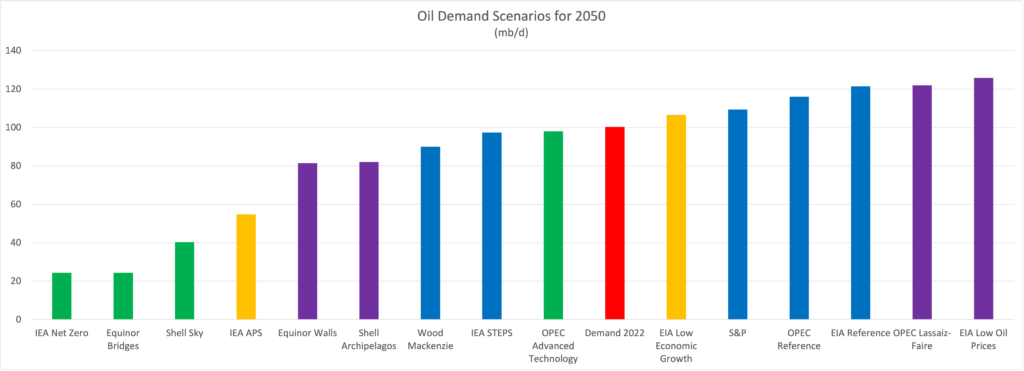

Admittedly: All consumption values for 2050 rank between the 24.3 and the 125.8 mb/d.

That is a difference of over 500% between the lowest and the highest consumption expected in mid-century.

This looks like a large range.

But all values at the lower end of the spectrum are from normative, transition-oriented scenarios.

They describe what needs to happen to achieve carbon neutrality in 2050, not what is most likely to happen based on current trends.

This holds for the IEA’s ‚Net Zero‘, Equinor’s ‚Bridges‘ and Shell’s ‚Sky‘ scenario.

(OPEC’s ‚Advanced Technology‘ scenario is also presumably ’net-zero‘, but arrives at a much higher value that is irreconcilable with the IEA’s path to carbon neutrality.)

Once the assumption of a successful net-zero strategy is relaxed, the scenarios start to show considerably higher demand by 2050.

Take, for example, the IEA’s ‚Announced Pledges‘ scenario.

This is a relatively pro-transition case, in which all governments fully implement their climate promises.

Even in this scenario, oil demand ends up being twice as large as it would be on an actual pathway to carbon neutrality.

But once scenarios focus on the policies that actually are in place, any future decline of oil demand fades into nothingness.

Even with the most optimistic baseline scenarios, oil consumption is not going to fall below 80 mb/d by 2050 – approximately the volume it had in the early 2010s.

The two most pro-transition company scenarios assume that, under given trends, the world will consume about 6 mb/d less in 2050 than in 2021.

This would seem a meager outcome of all these investments in e-mobility and green fuels.

But it is still the most optimistic value from the perspective of the energy transition.

Wood Mackenzie sees oil demand in 2050 at around 90 mb/d – the same value as in 2014.

Meanwhile, the IEA’s baseline STEPS scenario sees it at 97.4 mb/d – the same volume of oil consumption as in 2022.

For all the excitement, this is what ‚peak oil‘ most likely will to amount to:

A long-term stabilization roughly around the early 2020s‘ level of petroleum consumption.

Not so much a peak than an extremely long plateau.

(Although demand is of course going to increase above the 2022/2050 value before it comes down again.)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the scenarios of the non-European oil producers are most optimistic about the commodity’s future.

Almost all scenarios from the OPEC and the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) see consumption to remain above the 100 mb/d threshold until at least 2050.

This implies a continuously higher demand than in 2023.

The one exception is the OPEC’s pro-transition ‚Advanced Technologies‘ scenario, where the Organization presents its view on how to achieve net-zero by 2050.

Even under this condition, the OPEC still assumes that oil consumption will stand at 98 mb/d mid-century.

But the most likely case according to OPEC is a consumption at 116 mb/d in 2050 – about 14 mb/d more than 2023.

And this is still below what the Americans foresee.

According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), current trends and policies would lead to an oil demand of no less than 121.5 mb/d in 2050!

The bottom line of all this is clear:

Not a single scenario expects oil demand to go down significantly under given policies and trends.

Depending on economic conditions, it might even grow.

Are Alternative Fuels Going to Save the Energy Transition?

The main driver for any level of demand reduction is the expansion of electric mobility.

As such, it is also one of the most important factors that explain the different levels of expected demand in 2050.

The difference between the IEA’s and OPEC’s baseline scenarios, for example, mostly reflects their diverging assumptions on the future of e-mobility.

Just look at their predictions for the year 2030:

The IEA assumes that under given policies, no less than 240 million electric four-wheelers will be on the streets in 2030.

30% of all new vehicles in that year are supposed to be electric.

The OPEC’s baseline case, meanwhile, sees the overall number of electric vehicles in 2030 at 195.5 million – and that includes motorcycles and other two-wheelers.

The American EIA, which has the highest projected oil demand, does not discuss any specific number of future e-vehicle sales.

Instead, it argues that with given policies, future population and economic growth will far outweigh any effects of the climate transition.

The bottom-line here is clear:

Even the widespread use of electric cars barely manages to keep oil demand stable by 2050 – and even that only under the right economic conditions.

Given recent political developments, this implies that the future of oil might be even brighter than the scenarios anticipate.

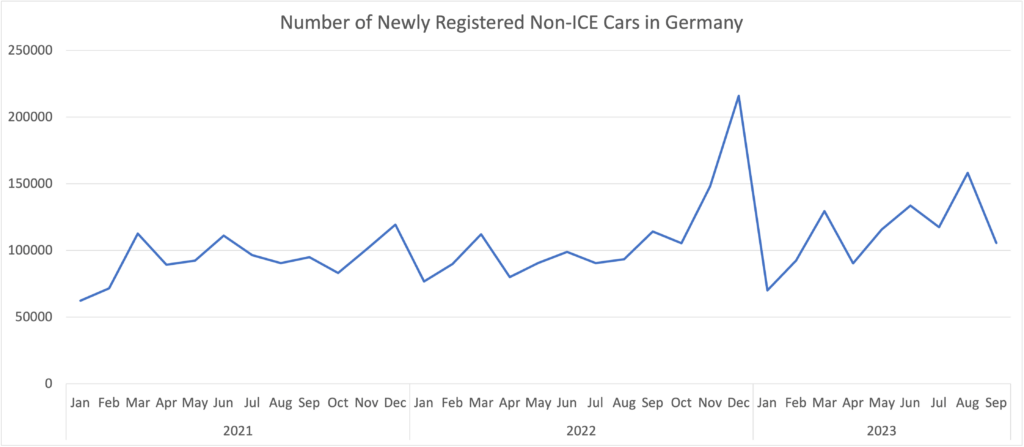

The fact is that demand for electric cars still highly depends on policy support – as two recent examples from leading electric vehicle markets illustrate:

In 2023, the German government phased out the financial support for commercially used electric vehicles.

It also announced a significant reduction in support for privately used electric vehicles, with especially larger models no longer qualifying for support as of 2024.

This did not immediately stop the increase of cars with other propulsion methods than the internal combustion engine.

But car dealers immediately reported declining orders of non-ICE vehicles, arguing that current numbers mainly reflect the execution of past contracts.

In China, a planned phased-out of subsidies of electric vehicles caused the number of new registrations to plummet in January 2023.

Compared to December 2022, new registrations of electric vehicles fell by half from 671,000 to 344,000.

This meant 8% fewer registrations than in January 2022, when that number stood at 375,000.

This marked the only year-on-year decline in at least 2022 and 2023.

Usually, the Chinese market sees growth rates of between 50 and 175%.

New registrations recovered after that, with both February and March seeing higher numbers than in same months one year earlier.

Nevertheless, the Chinese government announced that it would extend the tax credit until the end of 2027.

This is the third time that the credit, which exempts buyers of an electric car from the ten percent purchase tax, has been extended.

And while it is supposed to be halved between 2024 and 2027, the impact of such reductions on one of China’s key industries might just incentivize another extension.

Such developments point to an inconvenient truth for supporters of the energy transition:

With all the supposed dynamics of the electric vehicle market, the future of the transport transitions rests on continued political support.

And with the current rise of anti-transition policies across the West – including in the EU, where right-wing parties are still growing – that support is far from guaranteed.

In fact, even the German government with its strongly pro-transition Green party already watered down several climate policies.

It delayed, for example, an increase in the carbon price for transportation and heating fuel and abolished a report on the transition progress in the transportation sector.

All that in addition to the reduced support for electric mobility.

(And a recent decision by the country’s Constitutional Court has diminished funding for the energy transition even further.)

And if even proponents of the energy transition dial down their support, imagine what an actual pro-fossil government is likely to do.

The Bottom Line

Expect at the very least slightly rising to stable oil demand over the next years.

And always assume that political uncertainties are more likely to bring demand up rather than down.

Or, to put in a nutshell:

Expect oil to play a significant role in the global energy system for decades to come.