Water is at the Center of the Climate Crisis

„The climate crisis is primarily a water crisis.“ UN Water

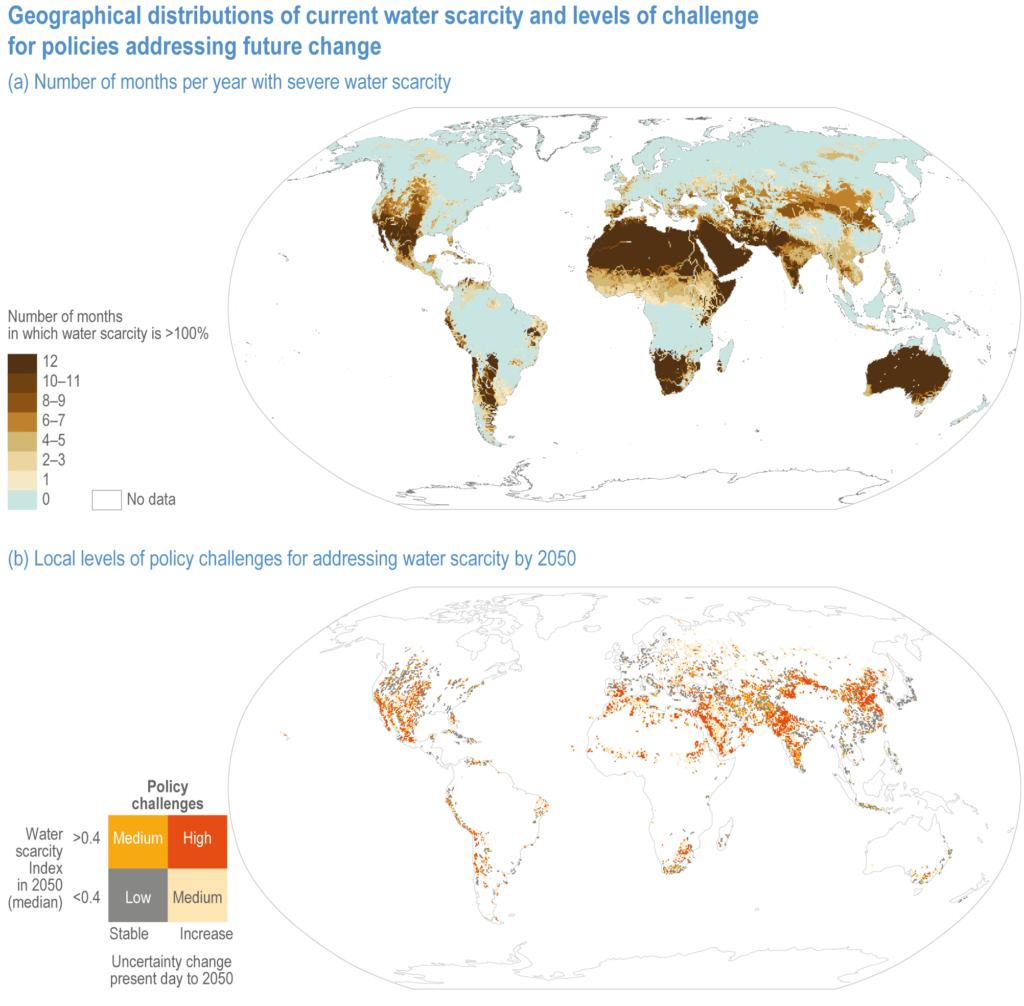

According to the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), around four billion people experience water scarcity ever year.

163 million people live in unfamiliar dry areas, with around 700 million people experiencing longer dry spells than they used to.

Not only become droughts more frequent. They also cause disproportional damage.

Between 1970 and 2019, droughts caused 34% of all disaster-related deaths, although they made up only 7% of all disaster events.

Already, lack of water is reducing global food production.

Around three quarters of the globally harvested area experiences yield losses due to droughts.

Overall, agricultural droughts have caused economic losses of no less than $166 bn since 1983.

But this pales in comparison to the loss of human lives.

According to the annual report by reliefweb for 2022, 2,601 persons lost their lives to water scarcity – more than double the annual average in the preceding decade.

(This puts droughts at the third place for disaster-related fatalities in 2022, after extreme temperatures with over 16.000 deaths and floods with 7.954 fatalities.)

But these number could be significantly too low.

A recent study found that the 2022 drought in Somalia might in fact have caused no less than 43,000 excess death.

Half of these occurred among children younger than five.

And things are just going to get worse.

The IPCC assumes that between three and four billion people will be exposed to physical – rather than just economic – water scarcity at global warming between 2°C and 4°C.

Extreme agricultural droughts would be twice as likely even at the increasingly unlikely threshold of 1.5°C global warming.

This would increase to a 150 to 200% higher likelihood at 2°C and rise even over 200% at 4°C.

Together with temperature changes, this could lead to three times higher risks to agricultural yields at a global warming of 3°C.

These developments are not going to stop at the EU border.

Even if most climate change-related deaths in Europe result from record temperature highs, increasing water scarcity does take its toll.

The European Environmental Agency (EEA) reports that between 1960 and 2010, renewable water resources per capita across Europe decreased by 24%.

Every year between 2000 and 2021, around 4.5% of the EU’s territory have been affected by droughts.

This situation is going to get worse, with the EEA estimating that heatwaves will increase, and summer precipitation will decrease until 2030.

There is no doubt that urgent climate action is required to resolved and mitigate global water scarcity.

At the same time, however, the energy sector is likely to increase pressure on global water supply – with some low-carbon energy sources being a part of the problem.

Future Energy Systems Will Need More Water

While most global water withdrawals result from agriculture, the energy sector is still a major consumer.

(Water withdrawal is the total amount of water taken from any underground or surface source.

It is different from water consumption, which refers to the water that is permanently lost to its source, e.g. through evaporation or use as drinking water.

Technologies might have a low water withdrawal but a high water consumption.)

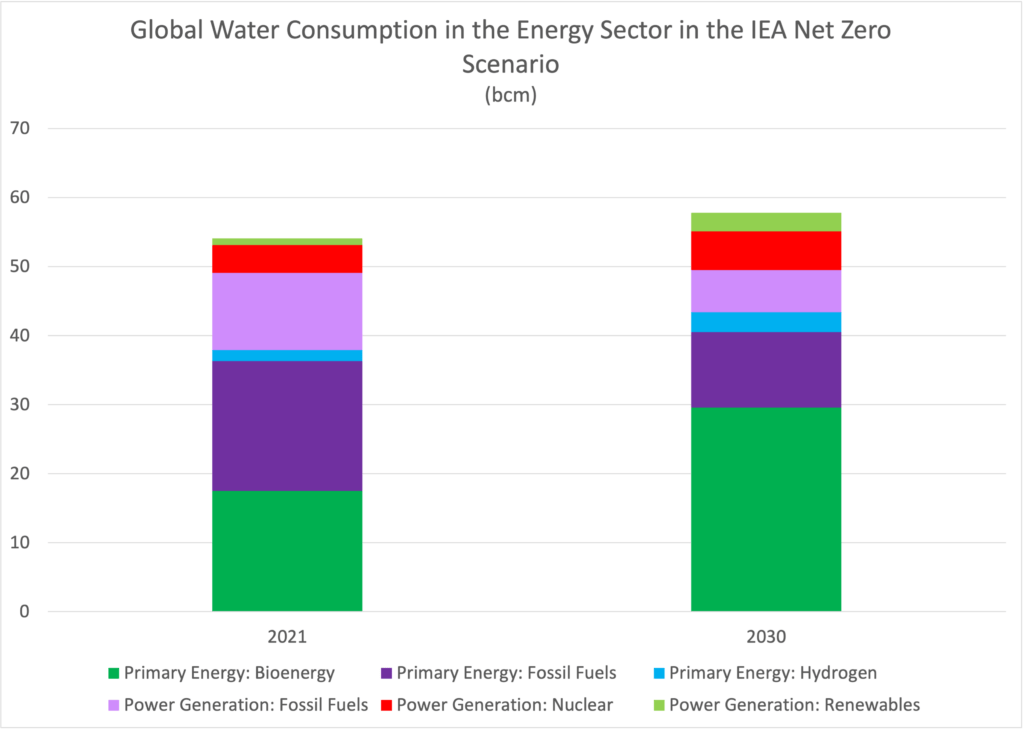

In 2021, 369.5 billion cubic meters (bcm) of fresh water were used in global energy production – corresponding to approximately 10% of global freshwater withdrawals.

With currently implemented climate policies, the IEA expects energy-related water withdrawals to increase by 6% to 393.2 bcm in 2030.

By far the biggest volumes are needed as cooling water in fossil and nuclear power production.

In 2021, cooling water accounted for 295.9 bcm or about 80% of all energy-related freshwater withdrawals.

With given climate policies, this value is expected to increase to 301.1 bcm in 2030, still accounting for more than three quarters of the sector’s freshwater needs.

(If global energy systems would become carbon neutral by 2050, that volume could go down to 248 bcm – the majority of which would be for nuclear.

This would still cover 70.6% of energy-related water withdrawals.)

In a scenario study published in 2016, Oliver Fricko and others analyzed the water requirements of energy transitions that could keep global warming to 2°C.

After remaining mostly stable until 2040, these requirements are most likely to increase by no less than 611% compared to 2020 until 2050.

Only one scenario has lower withdrawals by 2050 than in 2020 – pointing to the high likelihood of growing water needs for the future energy sector.

(These projections, however rest on energy scenarios from 2012 that foresee CO2-emissions peaking in 2020.

Actual values are likely to be higher.)

Median Water Consumption by Fuel Type

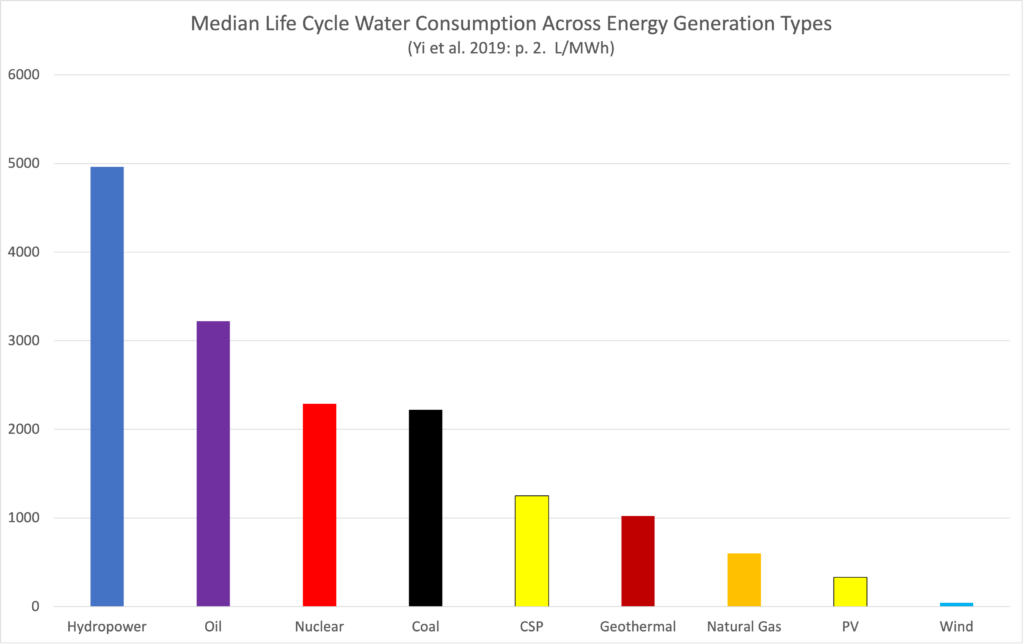

But the extent to which the energy transition will increase global water demand depends largely on the technologies applied.

A 2019 study by Yi Jin and others points to vastly different water requirements for different energy sources.

On one end of the spectrum is biomass with a median water consumption of more than 85,000 liters per megawatt hour (l/MWh).

(The high consumption for hydropower results from the evaporation of water from artificial reservoirs, which provide added value – e.g. for biodeversity and local climates – beyond energy generation.)

On the other end of the spectrum is photovoltaic solar power with only 330 L/MWh.

But the most water efficient energy technology by far is wind, which consumes only 43 liters per MWh over its life cycle.

The water consumption for fossil and nuclear power production are somewhere in between these two extremes, with natural gas having the lowest value in this group.

Gas is, in fact, even more water efficient than geothermal energy of Concentrated Solar Power (CPS), which consumes 1,250 liters per MWh of electricity produced.

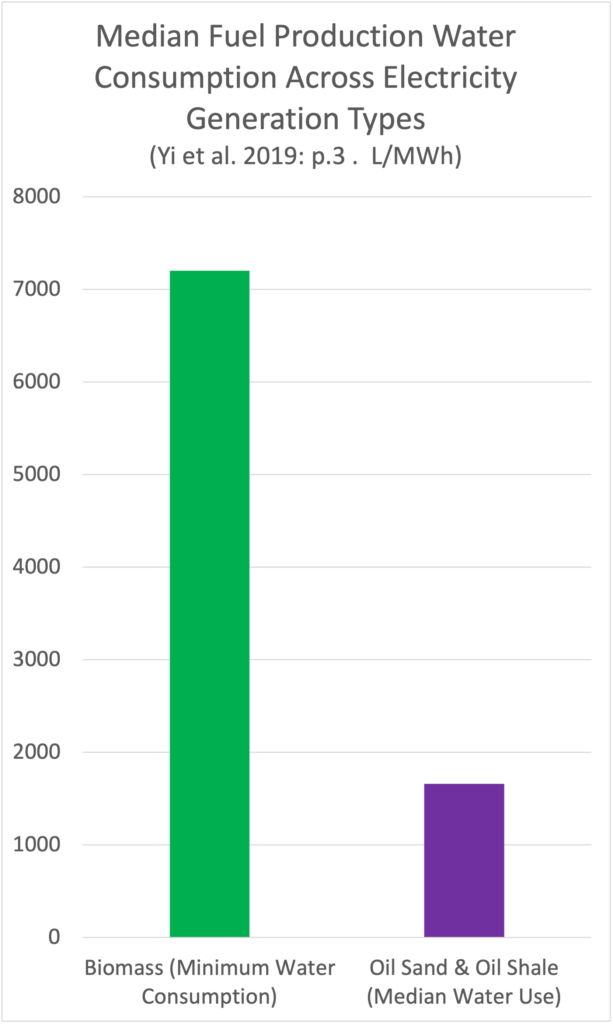

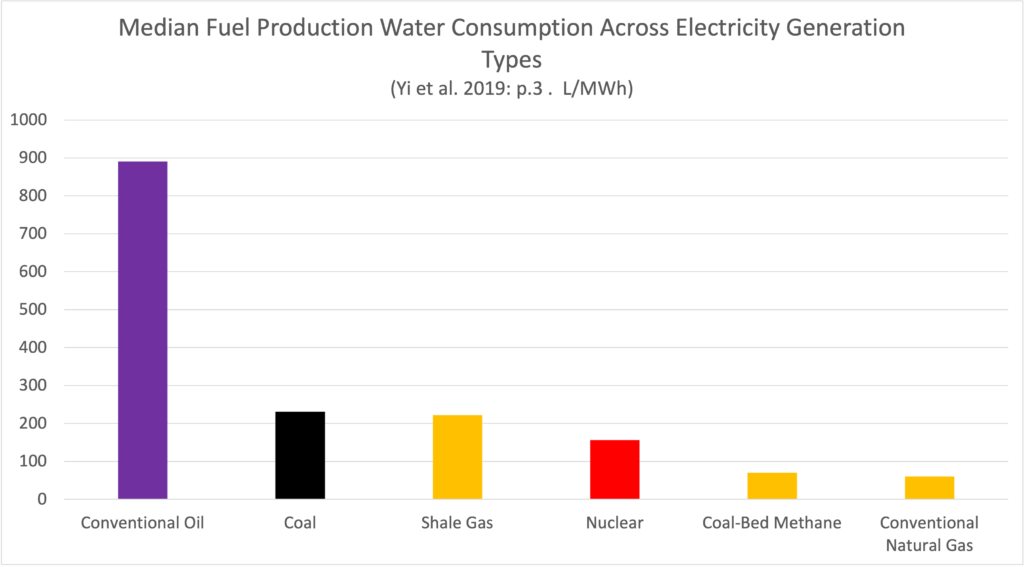

Water Consumption in Fuel Production

Looking at the water consumed for fuel production alone further illustrates the fallacy of using biomass in the energy transition.

Even assuming the lowest possible water consumption brings biomass production up to 7,200 liters per megawatt hour of produced power.

The most water intensive fossil fuels – oil sands and oil shales – require 1,658 L/MWh as a median value.

This is only a little more than a quarter of the lowest possible water consumption for biomass.

And this value covers overall water use, i.e., both water withdrawal and consumption.

Data for biomass, on the other hand, includes only water that is taken out of the liquid cycle for the foreseeable future.

All conventional fossil fuels need considerably less water.

Oil again has the highest value (891 L/MWh) and natural gas the lowest (60 L/MWh).

Obviously, wind and solar don’t need water to produce fuel.

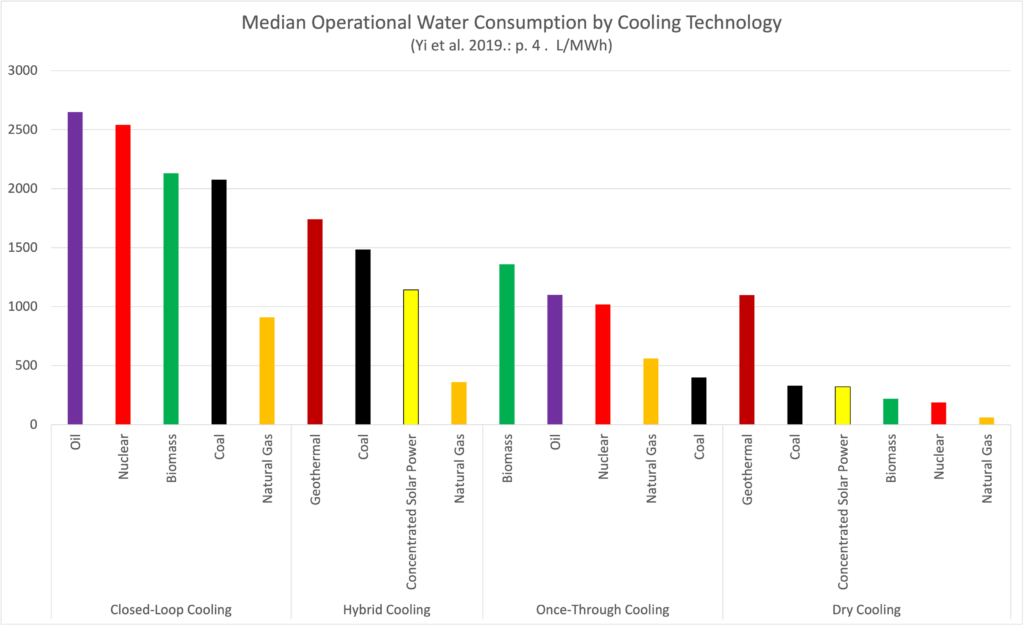

Cooling Technology Reduces Water Demand

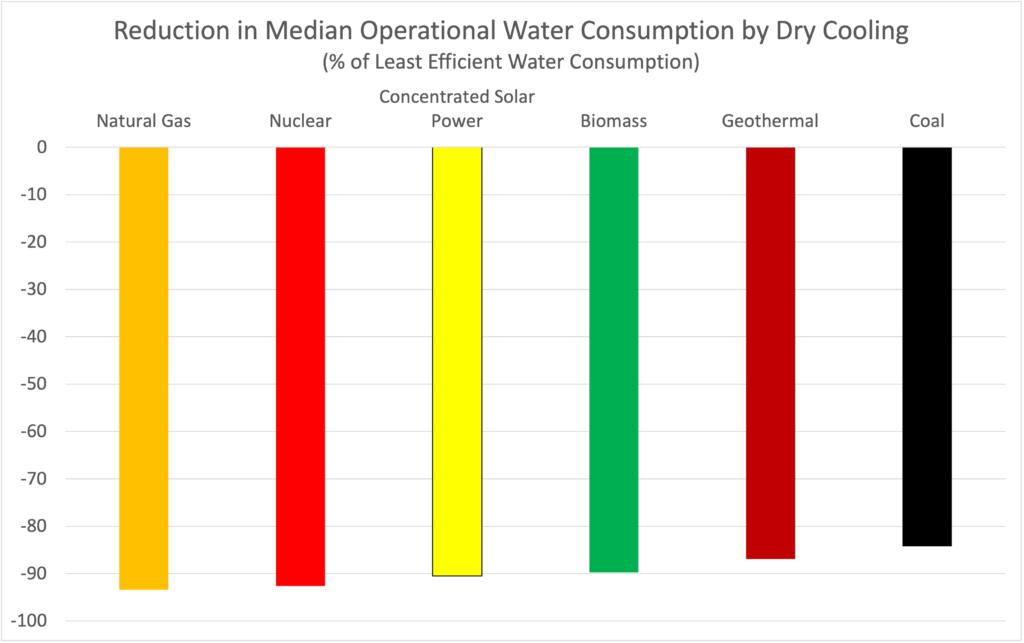

In their 2019 study, Jin and colleagues also found that dry cooling – an approach that uses air instead of water as cooling medium – enables massive water savings.

It brings down the consumption in natural gas and nuclear power generation by over 90% compared to close-loop cooling.

This reduces water consumption per megawatt hour from 2,542 liters to 189 for nuclear and from 910 to 60 liters for natural gas.

Dry cooling reduces water consumption for Concentrated Solar Power by 87% and for geothermal energy by around 90%.

Savings for CSP are already impressive, with 3,050 liters of water saved compared to wet cooling.

But geothermal energy achieves the highest reduction by far.

Dry cooling reduces its median operational water consumption by no less than 7,302 liters per megawatt hour – down to 1,098.

Dry cooling also reduces the operational water consumption for biomass in electricity generation by 90% down to 2020 liters per MW/h.

Not only is this still a high value.

It also does nothing to minimize the massive water requirements for generating the biomass in the first place.

But CCUS Brings Some Wastefulness Back.

Dry cooling goes a long way in making thermal power production more sustainable and should become mandatory in any new conventional or nuclear power plant project.

It does not, however, make fossil-based power production more climate friendly.

In fact, attempts to do so might severely counteract the water savings of more efficient cooling options.

Introducing CCUS to thermal power generation can increase operational water consumption by between 29 and 81%, depending on fuel and cooling technology.

The biggest increase is for natural gas plants using closed-loop cooling, while the highest overall operational consumption by far is for coal with closed-loop cooling.

In a 2021 paper, Lorenzo Rosa and colleagues estimate that the widespread introduction of CCUS would double humanity’s global water footprint.

While not technically exceeding available fresh water supplies, this would certainly exacerbate local scarcities and further intensify an inequitable global water distribution.

Water requirements are, however, not the same for each technology, with median consumption falling somewhere between 0.74 and 573 m3 of water per ton of CO2.

Again, fossil-based thermal power production has moderate water requirements for CCUS per ton of CO2.

Coal has in fact the highest water efficiency with 1.71 m3/ton CO2.

Gas uses somewhat more with 2.59 m3/ton CO2 but is still among the less water intense CCUS options.

(Water use goes further down when power plants combust their fuel in pure oxygen rather than air.

But this poses several operational challenges as well as higher costs that make the economic application challenging.)

Bioenergy with CCS (BECCS) has the highest water consumption, with medians ranging between 333 and 575 m3 of water per ton CO2.

The IEA assumes that BECCS capacities will reach 50 Mt CO2 in 2030 – still less than the Agency considers necessary to achieve net zero energy systems by mid-century.

But these 50 Mt alone imply an water use of between 16.7 billion and 28.8 billion m3 only for capturing the emissions of bioenergy.

An actual net zero development would require global BECCS capacities of no less than 190 Mt CO2 by 2033, which implies an annual water use of between 63.3 and 109.3 billion m3.

Introduce Dry Cooling and Avoid Biomass

All of this points to a clear pathway to reduce the water impact of future energy systems.

First: Focus on wind and photovoltaic solar – the two most water-efficient energy sources by far.

Other renewable energies, including geothermal energy and Concentrated Solar Power, have a worse water efficiency and should be used in a subsidiary and complementary role.

The same holds for nuclear, which, while climate friendly, has higher water requirements than coal and is therefore a less than ideal solution for the sustainability transition.

Second, avoid using biomass.

The extreme water requirements of biomass make it an unsuitable option for the energy transition.

Cooling technologies might reduce the operational needs, but do nothing to alleviate the water consumption of fuel production of carbon removal.

Despite its possible contributions to resolving the climate crisis, biomass is not a solution for sustainable energy systems.

Third, make the most water efficient cooling technologies mandatory – wherever feasible, this should be dry cooling.

Where dry cooling does not offer a feasible opportunity, the technology that has the lowest water consumption should be implemented.

Perhaps paradoxically, this might in some instances be once-through cooling, which withdraws more, but consumes less water than other options.

Making it mandatory in thermal power plants would go a long way in alleviating future pressure on global water systems.

Fourth, take care of the water/climate trade-off in thermal power generation.

As far as thermal power plants are still part of the future energy system, a careful deliberation needs to take place between the relative contributions of nuclear and natural gas with CCUS.

While nuclear energy is clearly the most climate friendly thermal option, natural gas has a higher water efficiency in all scenarios.

Even with the additional water demand of CCUS, natural gas still has less of a water impact than nuclear over the whole fuel cycle.

This balance should be carefully considered in any future investment decisions on thermal power plants.